| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of a giant chunk of glass in a museum room}

1 Caption: Bending Light

|

First (1) | Previous (3205) | Next (3207) || Latest Rerun (2874) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3206.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

I was at work a few weeks ago and my research division's general manager was chatting with a group of researchers about a talk he gave on cameras and optics to his son's primary school class, a group of 9-year-olds. During the question time at the end of his talk, one of the kids asked him, "How does a lens bend light?" My GM told us that he was unprepared for this question, and in the few seconds he had to think he couldn't come up with a good way to explain it that would make sense to a 9-year-old child. Everyone else in the conversation nodded sagely, murmuring things like, "Yeah, tough question," and so on.

What I was thinking was, "What an absolutely golden opportunity!" I must admit that I didn't come up with something immediately, but my mind was ticking over, and within about half an hour I had the essence of an idea for a way to do exactly that: explain how a lens bends light in terms a 9-year-old can understand.

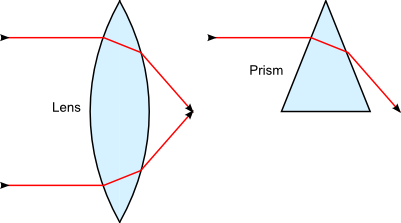

Figure 1. Light bending through a lens and a prism. |

So, lenses. The basic thing to understand about lenses is that they bend light. This is the principle behind their use in all sorts of devices, such as cameras, telescopes, microscopes, binoculars, magnifying glasses, and eyeglasses, which I think covers most of the applications people would immediately think of. These devices all gather light and allow you to look at objects in particular ways that you can't do otherwise. Lenses are also used in things like movie projectors, torches (flashlights for the Americans), car headlights, and lighthouses, to project beams of light. And the other important place you can find lenses is in eyes; you're reading this now through lenses in the front of your own eyeballs (unless you're using a screen reader).

If you examine some lenses, one thing you can notice pretty quickly is that they are all transparent, so that they let light pass through them. The next thing you might notice is that they all have curved surfaces. Here is an important hint about how lenses work.

Although, you don't need curved surfaces to bend light. There are other objects that bend light, which have flat surfaces. You may be thinking "a mirror!" It's true, a mirror changes the direction of a beam of light, but it does so by reflection. Reflection is when light bounces off a surface, like a rubber ball. Reflection is interesting in itself, but today we're talking about the sort of bending that happens to light when it passes through an object, not when it bounces off one. The things with flat surfaces that bend light are chunks of transparent material (glass usually) in triangle or wedge shapes, things we call prisms. The way a lens and prism bend light is shown in the diagram in Figure 1. Notice that the angle of the glass at the points where the top light beam enters and exits the glass are the same for both the lens and the prism. The way the glass curves (or is straight) away from that point doesn't matter for that beam of light. (It does matter for other beams of light that hit the glass elsewhere, which is where the difference between lenses and prisms comes into play.)

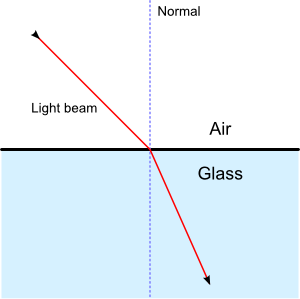

Figure 2. Light entering glass. |

This might seem a bit surprising, but the answer depends on how fast the light travels. How fast is that? When you turn on a light switch in a dark room, the light hits your eyes right away. It's so fast that you don't notice any delay at all[2]. Is it instantaneous? No, it's just very very fast. Light travels at a speed of close to 300,000 kilometres per second (km/s). That's fast enough to go around the world seven and a half times in one second (if it could curve around). That's pretty darn fast.

Only light doesn't always go that fast. When it goes through something, like glass or water, it slows down a bit. It's like when you are walking quickly and then suddenly there's a crowd of people in the way. You need to slow down to push your way in between them. Or when you're running down the sand on the beach and you enter the water, you have to slow down as it takes more work to move your legs through the water. It's a similar thing with light. As it moves through a material, it kind of has to push its way through the atoms. The more closely packed the atoms are, the more it has to push and the more it slows down, roughly speaking[3]. In fact, light only travels at its full speed when there are no atoms at all, in what we call a complete vacuum. The closest thing to a complete vacuum that we normally think about is outer space, though this still has a few atoms floating around.

The atoms in gases are pretty far apart. Light slows down only a very tiny bit in air; it's almost not even worth mentioning. But in glass, light slows down substantially, from 300,000 km/s to something under 200,000 km/s. The exact amount depends on the type of glass. So when light enters a piece of glass (from air), it slows down suddenly. It's just like running down the beach, then hitting the water and slowing down as you have to struggle to move your legs through the water. Okay, so what's this got to do with the light bending?

Imagine you're running down the beach with a group of friends, holding hands or with your arms linked together. You run side by side and at the same speed, so you form a nice straight line sweeping across the sand, straight towards the water. Now everyone in the line hits the water at the same time, and everyone suddenly has to slow down. That's fine, everyone slows down at the same time, so your entire line of friends, considered as a single object, just slows down, and everyone stays in line. This is just like what happens when light hits a piece of glass straight on. It just slows down.

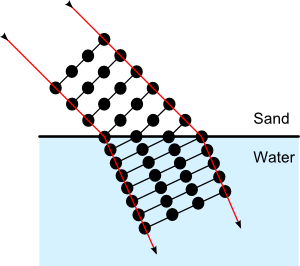

Figure 3. Line of people bending as they enter water. |

So if a line of people holding hands runs in one direction and hits something that makes everyone in the line slow down, and they hit it at an angle, then everyone ends up running in a different direction. The path of motion is bent. And that's pretty much what happens with a beam of light when it enters a piece of glass at an angle. The light is slowed down, and it slows down on one side of the beam before the other side, so the beam does a "crack the whip" and curves around, bending at the boundary.

The same thing happens in reverse when light goes from the glass back into the air. It's like running out of the water with your line of friends. If one end of the line emerges first, the people at that end can run faster than everyone else, so they swing around and the line ends up running on the sand in a different direction to what it was moving in the water.

There's one big difference between light entering glass and leaving glass though. Going in, the light is slowed down and always ends up bent towards what we call the "normal", which is simply a line at right angles to the air-glass boundary, as shown in the diagram. That's fine. No matter what angle you come in at, as long as it isn't directly along the normal, you can always bend a little bit more towards the normal. But imagine what happens if you and your friends are moving in a line out of the water at a a really big angle to the normal. The person on the end of the line steps out onto the sand first and starts running faster. If the line was at a small angle to the normal, the second person and third person and so on would emerge from the water soon after, and your line of people would bend as explained already. But now the second person doesn't emerge from the water for quite some time, and the person on the end, now running, has time to swing right around and enter the water again before the second person has had time to leave the water. The result in terms of an actual line of people is a big mess, but if you imagine the people can magically move right through each other, what you end up with is everyone moving back into the water, having kind of "bounced" off the sand, instead of emerging out onto the sand. And this is pretty much what happens to a beam of light as well, if it's heading from the glass towards the air at a big angle to the normal. It bounces off the surface and goes back into the glass. We call this total internal reflection.

Lenses and microscope. Museum of the History of Science, Oxford University. |

To finish off, let's return to the difference between lenses and prisms. I started talking about prisms because they have flat surfaces and it's easier to see what's going on when light enters a flat surface. All the light that hits a prism from the same direction hits a surface at the same angle, so the prism bends it all in the same direction. The result is that if you look through a prism, all the beams of light come out doing pretty much the same thing they were doing when they went in, just in a different direction. So a prism can bend light, but if you look through one it doesn't change the apparent size of what you're looking at.

Unlike a prism, a lens has a curved surface. So even if all the light comes in from the same direction, it hits the glass at different angles, which means it gets bent by different amounts. So the light coming out the other side of a lens is not just bent, it's kind of squashed, or enlarged. What this means is that when you look through a lens, it's as though the light is coming from an object that is closer to (or further away from) your eye than it really is. In other words, the object looks bigger (or smaller). Which is exactly what you want in a telescope, microscope, binoculars, and so on.

[2] At least, this is the case for old fashioned incandescent light bulbs. Fluorescent lights often take a second or two to warm up before they start working, but this time is related to the mechanism of turning the light on, not to how fast the light travels to your eyes.

[3] This is a simplified explanation suitable for 9-year-olds. Of course 9-year-olds know about atoms. You can bet they would if I was teaching them.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |