| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of tables and chairs arranged carefully outside a cafe}

1 Caption: Organising the Elements

|

First (1) | Previous (3207) | Next (3209) || Latest Rerun (2844) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3208.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Stuff is made of atoms, tiny particles that are too small to see. We can infer the existence of atoms from the chemical properties of matter, in particular how elements combine to form other substances. For many common compounds, the elements combine in specific fixed ratios, which can be understood as the combination of specific numbers of atoms of each element into molecules. This much we've discussed already.

Careful weighing of gold (wrapping with chocolate inside). |

As an example, take water, which has the chemical formula H2O. A molecule of water is made of two atoms of hydrogen combined with one atom of oxygen. An experiment might start by taking a jar of hydrogen and a jar of oxygen, and weighing them very carefully to determine the weights of the gases inside[1]. If you then combine and ignite the mixture, you produce as much water as the elements can make, leaving behind any leftover hydrogen or oxygen. You can then weigh the amount of water produced and any leftover gas, and figure out what weight of hydrogen and what weight of oxygen form the same weight of the compound water. If you do this accurately, you discover that water is made up of eight times the weight of oxygen as the weight of hydrogen. Since this represents twice as many hydrogen atoms as it does oxygen atoms, you can conclude that a single atom of oxygen weighs 16 times as much as an atom of hydrogen.

In reality, Dalton's experiments were a bit messier. His equipment wasn't quite up to the necessary precision, and he made the mistake of assuming that water was made of equal numbers of hydrogen and oxygen atoms. You can figure out the correct ratio by comparing the ratios among a number of different compounds using different elements, but it took the later work of the Italian chemist Amadeo Avogadro to really nail that down properly. As a result, Dalton's list of atomic weights (the relative weights of single atoms of different elements) were a bit screwy. But he was on the right track, and laid the important groundwork for what was to follow.

Amadeo Avogadro. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

They established quite early on that hydrogen had the lightest atoms, and so it made sense to express the weights of atoms of the other elements in terms of the weight of a hydrogen atom[3]. When they did this, assigning hydrogen atoms a weight of 1, atoms of some other elements they knew about came out roughly like this:

A whole number. (Actually not the atomic weight of any element; magnesium is 24.3, aluminium is 27.0.) |

We now have two different hypotheses about atoms and elements:

And to relieve the suspense, it was the first hypothesis that turned out to be incorrect. When chemists measured chlorine (a greenish gas identified as an element in 1810 by Humphry Davy), they got an atomic weight of 35.5 times hydrogen. At first many of them thought this was a mistake: surely it must be 35 or 36 exactly, and there was some error with the measurements. But despite ever more careful experiments, the number remained stubbornly at 35.5. So, reluctantly, the chemists had to give up their idea that atoms had nice whole number weights.

Dmitri Mendeleev, photographed in 1897. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

Some people had noticed these patterns before, but Mendeleev made the huge leap of leaving gaps in his "periodic table", where the properties of the surrounding elements didn't quite fit properly. The gaps, he said, were elements that had not yet been discovered. What's more, Mendeleev made the bold move of using the known properties of the elements surrounding the gaps to say what sort of properties he thought the missing elements would have - things like the melting point of the missing element, its colour, its density, what sort of compounds it would form, and so on. Specifically, in 1870/71 Mendeleev used this technique to predict the existence of:

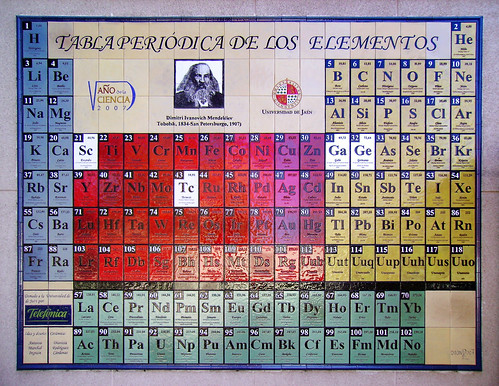

Periodic table mosaic at University of Jaén, Spain, commemorating Dmitri Mendeleev. The elements Mendeleev predicted are marked with white tiles: scandium, gallium, germanium, and technetium. (Adapted from photo taken by Wikimedia Commons user Kordas, released under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.) |

More elements continue to be found nowadays, at the heavy end of the table, where there is still room to expand (all the intermediate gaps have been filled in). The 101st element added was isolated in 1955 by a team of scientists working at the University of California in Berkeley. The team proposed naming it mendelevium, after Mendeleev. Team member Glenn Seaborg wrote later:

We thought it fitting that there be an element named for the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev, who had developed the periodic table. In nearly all our experiments discovering transuranium elements, we'd depended on his method of predicting chemical properties based on the element's position in the table. But in the middle of the Cold War, naming an element for a Russian was a somewhat bold gesture that did not sit well with some American critics.In 1997, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry ratified the name of mendelevium, ensuring it would be used forever to refer to this element.

The next step along our road to understanding what stuff is made of looks at the two hypotheses we listed above, and turns them into a couple of "whys":

Electricity.

[2] Now known to generations of high school chemistry students as the guy who gave us Avogadro's number.

[3] I'm being a bit loose here with the distinction between "weight" and "mass". Really, I'm using "weight" mostly because it's a more familiar word for most people. If you prefer to read it as "mass", that's okay. The difference between these two concepts is not really important at the moment, but will come up in later annotations when I talk about things like force and gravity.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |