| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of Wilhelm Röntgen's laboratory in the University of Würzburg}

1 Caption: Unravelling the nucleus

|

First (1) | Previous (3216) | Next (3218) || Latest Rerun (2874) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3217.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Some of the actual Crookes tubes used by Wilhelm Röntgen in his work on x-rays. Display in the University of Würzburg. |

Now we return to the fact that atoms are related to the chemical elements. John Dalton and his contemporaries had established by around 1803 that there were dozens of elements, and that they were distinguished by the types of atoms that comprised them. Furthermore, the atoms of each element had different masses - and most of those masses appeared to be very, very close to whole number multiples of the mass of a hydrogen atom, but not all of them. This observation remained a mystery right through the unravelling of the electron and the first attempts at understanding the structure of an atom.

Another mystery that came into play in the late 19th century was the discovery that some elements emit various types of radiation. In 1896, Henri Becquerel was performing experiments with uranium, an unusual element discovered in 1789. It had the strange property that some particular salts (i.e. compounds) of uranium, after being exposed to light and then moved to a dark room, emitted a glow of light. This had been known for some time and was called phosphorescence, since it could also be seen in some compounds of phosphorus. Becquerel thought that if he exposed these phosphorescent uranium salts to really bright sunlight, then they might emit x-rays, a strange and powerful radiation that Wilhelm Röntgen had discovered in Würzburg, Germany, just a few months earlier. His first experiments seemed to indicate exactly this: After exposing some uranium salts to strong sunlight, then placing the uranium next to a glass plate covered in photographic emulsion shielded from light, the emulsion showed signs of having been exposed. Furthermore, putting pieces of metal like coins between the uranium and the plate produced shadows of the metal on the plate.

Henri Becquerel. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

This is often cited as one of the great examples of serendipity in the annals of science. Becquerel's initial observations with the sun-exposed uranium perfectly matched his hypothesis that phosphorescent uranium salts exposed to strong light would emit x-rays. Naturally he was delighted, but being a good scientist he wanted to repeat his observations. By sheer chance he performed a modification of his experiment that revealed something even more astonishing. However, Becquerel was a careful and meticulous investigator (as revealed by his notebooks). If he had established that phosphorescent uranium salts produced something like x-rays after being exposed to the sun, he would almost certainly have tried the experiment without the sun exposure, to establish that it was the sunlight causing the phenomenon. At this point he would have made the same discovery: It was not the sunlight at all; the phosphorescent uranium salts emitted x-ray-like radiation all the time.

Furthermore, even given the serendipitous nature of how this discovery actually happened, Becquerel continued his investigations methodically by examining non-phosphorescent uranium salts - different compounds of uranium that did not glow after being exposed to light. These experiments showed that these salts also produced strong exposure and metal shadows on photographic plates. The conclusion by now was plain: it was the uranium itself, not just some of its compounds, and it emitted powerful radiation all the time. Henri Becquerel had discovered the phenomenon of radioactivity.

Marie and Pierre Curie were at the forefront of an international effort to investigate this effect. Marie's first discovery was that the amount of radiation produced depended only on the amount of uranium present; it was completely independent of what other elements it might be combined with, and in what proportions. This established that the radiation was a property of the uranium atoms alone, and not a chemical reaction with other elements. There were two exceptions: the two natural uranium ores called pitchblende and torbernite emitted more radiation than could be explained by their uranium content. Marie hypothesised that these minerals contained some other, unknown, element that was also radioactive. By 1898, Marie and Pierre had processed enough pitchblende to announce the discovery of not one, but two new radioactive elements, which they called polonium and radium[1]. Like uranium, these elements were dense, heavy metals, and they spontaneously emitted a range of different radiations with distinctive properties.

Pierre and Marie Curie, and daughter Irène. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

The second type of radiation, dubbed beta radiation could pass through air and paper, but was stopped by a thin sheet of metal. Becquerel showed this radiation to be made of particles much lighter than alpha particles and negatively charged - in fact beta particles are electrons. The third type of radiation, gamma radiation, was initially more mysterious. It had no electric charge and could penetrate anything up to slabs of lead. It was related to Röntgen's x-rays. In 1910, Rutherford established that both x-rays and gamma rays were forms of electromagnetic radiation, essentially the same as light, but with shorter wavelengths and much higher energies.

In 1917, Rutherford performed experiments using alpha particles to bombard various other gases. When the target was hydrogen, it emitted positively charged particles with almost the same mass as hydrogen atoms. These must be hydrogen nuclei, with an electron stripped off. But then Rutherford discovered that nitrogen produced some particles with exactly the same properties. This showed that nitrogen atoms contained within them something that was identical to hydrogen nuclei. From this observation, Rutherford proposed in 1920 that the nuclei of atoms might all be composed of hydrogen nuclei making up the mass, plus a number of electrons (known to be much much lighter) to cancel out the excess charge. Hydrogen nuclei would be an important fundamental new particle then, which he named the proton. A helium nucleus would be made of four protons and two electrons. And so on for heavier elements.

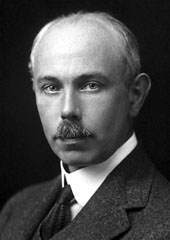

Francis William Aston. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

The next clue to unravelling the structure of the nucleus came in the work of Francis William Aston, a co-worker of J. J. Thomson at Cambridge. He investigated the idea of Frederick Soddy from the University of Glasgow that the elements might come in different "types". These types had the same chemical properties, but different atomic masses. This went against everything known about atoms at the time, but Soddy was led to this conclusion to explain some otherwise inexplicable properties of radioactive uranium decay. Soddy called the different types "isotopes". What Aston did, in the years either side of World War I, was to build a device capable of accurately distinguishing the masses of atomic nuclei. He discovered that many elements could be separated into a more common isotope, and one or more rarer isotopes of different atomic masses.

In 1930, Walther Bothe discovered that beryllium bombarded with alpha particles emitted an electrically neutral radiation, which he assumed was gamma radiation. In 1932, Irène Joliot-Curie (daughter of Marie and Pierre) and her husband Frédéric discovered that this radiation could eject high-energy protons from material containing hydrogen.

This discovery came to the attention of James Chadwick, a British scientist working at Cambridge University. He analysed the reactions and concluded that the neutral radiation could not be gamma rays. He performed further experiments and determined that the mysterious radiation was made of electrically neutral particles, with mass slightly larger than a proton. The name "neutron" for such hypothetical particles had already been suggested by Rutherford, but here was the first direct evidence that such a particle actually existed.

James Chadwick. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

For example oxygen with 8 protons and 8 neutrons, and thus an atomic mass very close to 16[3], is by far the most common isotope of oxygen. But there is also oxygen with 8 protons and 9 neutrons, with an atomic mass of 17, and oxygen with 8 protons and 10 neutrons, with an atomic mass of 18. But these heavier isotopes together make up only a fraction of a percent of all the oxygen in any normal sample. So the measured atomic mass of a random sample of oxygen is very close to 16.

Chlorine is a different story. It has two common isotopes: 17 protons plus 18 neutrons for an atomic mass of 35, and 17 protons plus 20 neutrons for an atomic mass of 37[4]. The first is close to 75% of naturally occurring chlorine, while the heavier isotope makes up 25%. This combination gives an average atomic mass of 35.5.

So finally, in 1932 - just 80 years ago - we had finally understood a basic property of atoms, and had completed our discovery of the three subatomic particles that comprise pretty much all of the matter around us[5]. A hundred or so disparate chemical elements, with widely varying properties, could now be understood to be combinations of just three different particles: negatively charged electrons, positively charged protons, and electrically neutral neutrons, arranged into the different atoms that make up the elements.

80 years ago. You might have grandparents or other relatives who are older than that. People you know who were alive before we understood what atoms are made of. The progress we have made in our understanding of the world around us in the last hundred or so years is astounding. And there's plenty more to tell.

[2] These are the mysterious "positively charged helium atoms" I mentioned in an earlier annotation that Rutherford's students Geiger and Marsden used in 1909 for the gold foil experiment. They were alpha particles emitted by radon.

[3] Remembering that a neutron is only very slightly heavier than a proton.

[4] Chlorine can also exist with 17 protons plus 19 neutrons (atomic mass of 36), but this isotope is radioactive and decays into argon over tens of thousands of years, so there's virtually none of it left on Earth any more.

[5] Not quite all of it, but what's left over is not something we experience directly and is a story for another day. Everything we can see and touch is made of electrons, protons, and neutrons, usually arranged into atoms.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |