| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of Stonehenge}

1 Caption: Cycles of the Year

|

First (1) | Previous (3277) | Next (3279) || Latest Rerun (2895) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3278.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

A gibbous moon, late afternoon, southern hemisphere. |

Another large, bright object in the sky has a cycle too. The moon rises and sets like the sun, but it does it slightly more slowly. The result is that the moon rises later each day. It also changes shape, tending to be fuller at night and more like a crescent during the day. The rising and setting pattern of the moon and its changes of shape are synchronised.

On some particular day the moon will rise around sunset and be full. The next day it will rise later, waning, or reducing in shape. Its shape at this time is described as gibbous. Roughly seven days later the moon is a semicircle (what we call a quarter moon, for reasons that puzzled me intensely as a child. After all, it's half the moon we normally see!) and rises in the middle of the night. Another seven days later the moon has become a thin crescent rising about the same time as the sun, and may disappear from obvious view altogether. From here it begins waxing, or becoming fuller again.[1] Seven more days, and the moon is the other semicircle, and rising in the middle of the day. And after yet another seven days, the moon has returned to full, rising at sunset once more.

A full cycle of the moon takes about 29 and a half days. This is where the concept and word "month" comes from, although in our modern calendar almost all the months (apart from February) have become slightly elongated so that they no longer match the moon very well. The lunar cycle is also about the same length as the human menstrual cycle - a coincidence noted by many ancient groups of people and used as the basis of various myths and legends. It's also the derivation of the very word "menstrual" itself, "mens-" coming from the Latin "mensis" meaning "month", itself originally from the Greek "mene" meaning "moon".

Wintry landscape. |

All of these things were very important to our hunter-gatherer and agricultural ancestors. The warm periods were times of plenty, with food easy to collect and little shelter from the elements necessary. The cold times were harsh, with food harder to come by and deadly cold to avoid. These times became known as summer and winter (or their equivalents in other languages) and the cycle that connected them was the year.

Without a calendar to keep track of the days, a year can feel very imprecise. The most obvious markers are the changes in weather and the growth of plants. But these can vary from year to year, with some years having longer summers and shorter winters, or vice versa. If you count the days very carefully over many years that you can show that each year is roughly the same length. To be more precise, you need astronomy.

Sunrise. (Unfortunately the guy moved so I couldn't track his shadow throughout the year.) |

The sun rises in the east, moves in an arc across the sky, and sets in the west. If you trace the path of the sun on any given day, it moves as though the sky were the inside of a great sphere and the sun was moving along a circle defined by the intersection of this "sky-sphere" with a plane.[2] That plane is tilted - the sun does not rise straight up perpendicular to the ground, it does not rise all the way up to the highest point of the sky directly overhead, and it does not set straight down.[3] The sun rises moving at an angle to the horizon. If you live in the southern hemisphere and watch the sunrise, the sun moves to the left as it climbs higher in the sky. If you live in the northern hemisphere, it moves the other way, to the right. It maintains this motion throughout the day. If you turn to face the sun all day, from sunrise to sunset, you will turn anticlockwise in the southern hemisphere, or clockwise in the northern.[4]

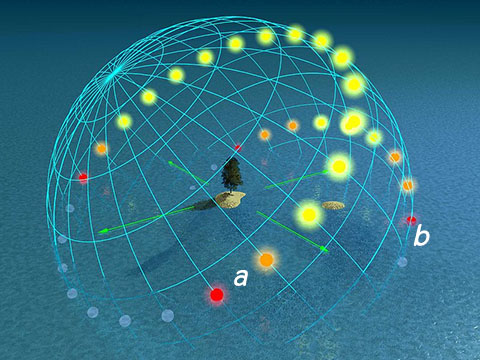

Planes of the sun's motion at the summer solstice (a) and winter solstice (b). Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike image by Wikimedia user Tau'olunga from Wikimedia Commons. |

Only twice per year, in between the two extreme seasons, does the sun rise due east, move across the sky, and set due west. In the southern hemisphere, in summer the sun rises south of due east, moves across the sky to the left so that in the middle of the day it is high in the sky to the north, and then sets south of due west, while in the winter it rises north of due east, stays to the north all day, and sets north of due west. In the northern hemisphere this is reversed: in summer the sun rises north of due east, moves across the sky to the right so that in the middle of the day it is high in the sky to the south, and sets north of due west, while in the winter it rises south of due east, stays to the south all day, and sets south of due west.

In other words, it seems as if the plane defined by the sun's motion wobbles up and down. If you stay in the same location on Earth, the plane doesn't change its tilt. It moves up and down, always staying parallel. One cycle of this wobble takes one year. The highest position of the plane corresponds to the day of maximum time between sunrise and sunset in the summer. This is the same day of the year when the sun rises and sets furthest to the south (in the southern hemisphere) or north (in the northern). Similarly, the lowest position of the sun's plane occurs in midwinter, on the day of least sunlight, when the sun rises furthest to the north (in the southern hemisphere) or south (in the northern).

There are four special days (or more precisely, times) defined by this yearly motion of the sun. The maximum daylight midsummer day is called the summer solstice. The time of year this occurs is very precise but, because the year is not an exact number days in length (for which we compensate with leap years) and because different parts of Earth have different time zones, the date on our calendar on which it occurs can vary slightly. In the southern hemisphere, the summer solstice occurs on December 20, 21, 22, or 23, while in the north it occurs on June 20, 21, or 22. The day of minimum daylight in winter is similarly called the winter solstice, and it occurs at the same time as the summer solstice in the opposite hemisphere.

Autumn leaves. |

Without modern timekeeping technology, and relying only on the movements of the sun, the equinoxes are difficult to pin down. But the solstices are easier. If you have a fixed object somewhere, you can observe the shadow it casts at the moment of sunrise every day. If you live in the southern hemisphere, then as the summer solstice approaches the sun is rising further to the south every day, which means that the object's shadow at sunrise shifts slightly to the north each day. At the solstice, the sun is at its most southerly point in the yearly cycle, and begins moving north again on the following days. So the shadow reaches a most northerly position at the dawn of the solstice, and then begins moving south again. (Reverse north/south if you are in the northern hemisphere.)

This observation allows you to mark the northernmost position of the shadow, on the day of the summer solstice. This position is repeated precisely on the sunrise of the summer solstice one year later, and so on every year, at intervals of exactly one year. So by observing the position of the sun in this way every day, you can measure the year precisely. This then allows you start making accurate predictions such as roughly how long the warm weather will continue before turning cold again as winter approaches, or how soon the winter will begin breaking into spring.[5]

Stonehenge. |

So the cycles of the year became very important to our ancestors. In a very real sense, astronomy allowed early humans to develop sustainable agricultural societies. This development in human culture, and the industrial societies it would later enable, would have been significantly more difficult without people observing the patterns of the movements of the sun. Given this, it's little wonder then that our pre-industrial ancestors placed so much importance on the role of the sun in their lives, in many cases considering it some form of life-giving god.

The early astronomers who observed the movements of the sun often became conflated with religious leaders, and the observations of the solstices became marked with ceremonies and celebrations. Many early civilisations built special observation stations, designed to make it easier to note the movements of the sun throughout the year, often involving careful arrangements of stones, lined up so that the shadows cast by the solstice sunrises would fall on significant marked spots. One of the most famous such places is Stonehenge, in the fields of Wiltshire, England. Here, the summer solstice sunrise aligns spectacularly along the main axis of the stone circle to another stone, the Heel Stone, placed several metres outside the circle. But places with similar alignments to the sun can be found all over the world.

And it's no wonder. Astronomy and the yearly cycle were important to ancient civilisations because it was a matter of staying alive.

[2] The sun's path relative to the Earth (i.e. if we assumed the Earth was stationary) is actually an ellipse, but an ellipse which is very close to circular. For the purposes of today's annotation the difference is not important, so I'm just going to call it a circle. For those of you who know about such things, this means I'm ignoring the things like the equation of time today.

[3] If you live in the tropics, the sun can do all of these things.

[4] It's often stated that this is essentially the reason that clock hands go clockwise, since the people who invented clocks lived in the northern hemisphere and the shadows on sundials there move in the same manner as the sun which casts the shadow. While this may perhaps be true, it is not conclusively documented. In particular, there are known examples of early clocks on which the hands go around the other way.

[5] What I mean by "accurate predictions of roughly how long the warm weather will continue": Weather is notoriously difficult to predict day to day. But seasonal trends are much more predictable in the sense that if it's the summer solstice today, then you can say that the weather will start to get significantly colder in, say, three months (depending on your local overall climate). That turn in temperatures might occur in 2.5 months, or 3 months, or 3.7 months... but averaged out over many years you'll always be pretty close.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |