| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of steel beer kegs}

1 Caption: Metallic bonds

|

First (1) | Previous (3302) | Next (3304) || Latest Rerun (2895) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3303.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

An analogy to metallic bonding. The cherries are like the metal ions, and the cream and pastry is like the electrons. |

These types of bonds cover two cases: atoms needing extra electrons to fill a shell bonding with other atoms needing additional electrons, and atoms needing extra electrons bonding with atoms having a few extra to spare. In each case by "extra" I am referring to the number of electrons needed to make a complete electron shell, not the number needed to balance the number of protons in the nucleus (which is how many an electrically neutral atom would have).

The third case also exists: atoms with extra electrons over their last complete shell, bonded with other atoms with extra electrons. This situation is also very common. It occurs wherever you have a lot of atoms with such extra electrons. Elements whose atoms contain a few electrons more than a complete shell are called metals. Metal atoms bond with each other in a very different way. The extra electrons of each atom are held relatively loosely, and can easily slip between adjacent metal atoms. The result is a kind of loose soup of electrons. We've already seen how this electron soup leads to the property of electrical conductivity. It also serves as an electrical glue, holding the atoms together. Without the loose outer electrons, each atom would be a positively charged ion. These ions are held together by the surrounding negatively charged electron soup, like atomic meatballs in a thick electron sauce.

Copper bull's head sculpture, British Museum, London. |

Similarly in an ionically bonded solid, like salt. The sodium atoms can donate one electron each, and the chlorine atoms need one more electron each. So in a sample of salt, you end up with pretty much identical numbers of sodium and chlorine atoms. You can't add more chlorine and make a salt which is "more chloriney" than regular 1:1 sodium chloride.

For a metal it's different. The electrons are loose and not specifically associated with any given atom for very long. This makes the crystal structures of metals somewhat loose and flexible as well. Salt crystals form lovely cubes, with each sodium atom surrounded by exactly six chlorine atoms, and vice versa. This makes the typical cubical shape of salt crystals which are easily observed with a magnifying glass.

If you take a typical ionic or covalent crystal like salt—or quartz, which has much bigger crystals—and you try to bend it or crush it with enough force, it will break. You actually rip the atomic bonds apart and snap or crunch the crystal into two or more separate pieces. Metals behave very differently. Bend a metal and it will bend without breaking. Crush a metal and it will deform, oozing into a different shape, without crunching into pieces. The looseness of the electron soup means the atoms can slip around a bit without breaking apart. They can flow and move to new configurations and shapes, without losing the electrostatic cling between the ions and the electrons that holds the material together. It's like the difference between a potato crisp and a thin slice of raw potato. One is hard and crunchy, the other is soft and flexible.

The softness of metals is relative to covalent and ionic solids. Most metals still feel pretty hard to us, but some are soft and flexible enough to bend under our hands, particularly in very thin pieces like steel wool, sheets of lead, or aluminium drink cans. This metallic ability to bend and stretch without breaking is called malleability (or, specifically for stretching, ductility), and is in contrast to the property we know as brittleness. Some metals are more malleable than others. Gold and copper can easily be bent and hammered and worked into various shapes, while zinc is more brittle. (The word "malleability", by the way, comes from the Latin malleus, meaning "hammer".)

Gold and copper also share another property. They can occasionally be found in their elemental form in various places on or just under the surface of the Earth. They were among the very first metals used by humans, approximately 9000-7000 years ago. Gold is a bit too soft to be used for much other than decoration, but copper is hard enough to make into usable tools and weapons. What's more, you can extract copper from copper-containing rocks by heating them up in a fire until the copper melts and runs free. This was the first metal humans learnt to smelt from ore, and it became the basis of a technology period known as the Chalcolithic. Copper tools are not great though, because copper is still pretty soft and doesn't hold a sharp edge very well. Nevertheless, it was better than stone for many purposes because it wasn't as brittle.

Bronze statue of Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, Capitoline Museum, Rome. |

For metals, however, the movement of electrons is much less constrained. As long as an atom has a few electrons to donate to the electron soup surrounding the positively charged metal ions, it can sit in the structure. So you can mix, for example, copper and tin atoms together in pretty much any proportion you like, and they will form a coherent metal. The way to do this is simple: melt some copper and some tin, mix them together, and let the resulting mixture harden. You end up with a metal that is part copper and part tin, but which looks like a single metal. Such a metal, made of different metal atoms mixed together, we call an alloy. In the case of copper and tin, we call the alloy bronze.

The thing about an alloy is that the properties of the resulting metal are often different from the properties of the constituent elements. Copper and tin are both fairly soft, malleable metals. But mix them together to form bronze, and you end up with a significantly harder and more durable metal. Bronze can hold a sharpened edge better than copper. When early human cultures around the Mediterranean discovered how to make bronze, they quickly adopted it as the metal of choice for tools and weapons. The brief age of copper gave way to the Bronze Age, which lasted from roughly 5000 to 2500 years ago. (Different cultures around the world went through this phase of technology at slightly different times.)

The properties of bronze vary depending on the proportions of copper and tin. By experimenting with different mixtures, you can find out that the optimum ratio for hardness and durability is about 90% copper to 10% tin (it can vary quite a bit). Determining the best ways to make useful bronze was one of the first applications of science used by humans.

Bronze was relatively easy to discover and make, because the melting points of copper and tin are both fairly low, as metals go. You can melt and mix them over a normal sort of fire. The next metal technology breakthrough had to wait until we figured out how to make significantly hotter fires. By blowing extra oxygen onto a confined fire with bellows, and using charcoal instead of raw wood as fuel, you can make it burn hotter. The extra heat brings more metals into melting range, including, critically, iron.

Iron is more chemically reactive than copper, which means that almost all of the iron on or near Earth's surface is found in compounds with other elements. Iron has to be extracted from ore. To do this, you need to heat the ore up hot enough to melt the iron. And this can only be done with extra hot fire technology, using bellows forced fire in a smelter. But the benefits of extracting iron were worth the effort. Iron is much easier to find than copper or, especially, tin - it's virtually everywhere. Even though bronze is harder than iron, iron is hard enough, and it's much easier to equip an army with iron swords than bronze ones. Once Bronze Age civilisations realised this and began working iron, they left the Bronze Age and entered the Iron Age.

The Eiffel Tower is made of wrought iron. |

One of the most important things that iron can alloy with is carbon. Carbon is not exactly a metal itself, but in small quantities it sits okay within a metallic compound. It has a half-filled shell, with four out of eight electrons, which is what makes it such a versatile element and the basis for organic chemistry. Adding a small amount of carbon to a metal alloy can work because some of the four electrons can take part in the metallic bond. Humans discovered this by accident, because one of the things that is abundant in the heat of a smelter is carbon from the burning charcoal (or coal) is carbon. Some of it ended up mixed with the molten iron, which produced various iron-carbon alloys. The first such alloy used by people was wrought iron, which contains about 0.1% to 0.25% carbon.

Wrought iron is strong, tough, and malleable. It can be heated and worked in a forge by blacksmiths to make all manner of utensils, from weapons to horseshoes and ploughshares. It's easy to weld pieces of wrought iron together by heating them to red heat and hammering them together. Wrought iron is very useful, but it tends to corrode very quickly, becoming rust, which is iron oxide, and its not as hard as bronze. But people quickly learnt that the iron they produced could be made to have very different properties, by treating it in various ways during and after production. These processes were used haphazardly by several different civilisations prior to 500 BC, before being systematically used in India after that date. Medieval Europe later caught up with the technology. What they were now producing was an alloy that would change the world: steel.

Stainless steel resists even the corrosiveness of sea water. |

Adding in a little bit of certain other metals makes steel even more useful. Adding around 10% chromium makes the resulting alloy much more resistant to corrosion. You have some of this alloy in your home - we call it stainless steel. There are many different types of steel, their properties determined by the other elements included in the alloy and their relative proportions. Some steels containing tungsten are incredibly hard and are used for things like drill bits and machinery that bores through rock and concrete. Other steels are more flexible and are used for things where shock absorbency is important, such as springs and car bodies.

This is the cool thing about alloys in general. By mixing metals in the infinitely variable proportions available, we can tailor alloys for almost any property we desire in a material. You might imagine that if you mix two metals, the resulting alloy would have properties somewhere in between the two base metals. In many cases this is true, but for some physical properties such as hardness or melting point, the alloy can be surprisingly outside that range. We've already mentioned bronze, which is harder than either of its constituent metals, copper and tin. Similarly, by mixing metals such as bismuth, lead, tin, and cadmium, you can produce an alloy known as Wood's metal, which has a melting point significantly lower than any of them. Why is this useful?

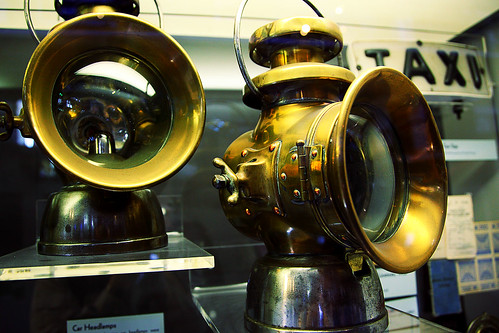

Antique brass car headlamps, designed to resist corrosion. |

There are many other alloys with useful properties that no elemental metal has. Aluminium is very light in weight, and would have been ideal as the structural material in Zeppelins, if only it had been strong enough. To make it stronger, you can add small amounts of copper, magnesium, and manganese, to make the alloy known as duralumin, which is what the skeletons of zeppelins were actually made of. There are alloys designed to be non-reactive inside the hostile environment of a human body, so they can be used for things like replacement hip joints and strengthening bones. Then there's brass, another alloy of copper, only this time with zinc, not tin. Brass resists salt water corrosion so well it is used for many of the fittings on ships. The coins in your pocket are made of alloys, designed to resemble silver and gold, but be much longer wearing. Speaking of gold, although it's a beautiful metal, it is much too soft to be used routinely for jewellery in its pure form. So it is alloyed with silver and copper to produce harder metals that can stand up to the wear and tear of daily use.

Metals are an extremely diverse and useful group of elements, and the metallic bond means that the alloys they form come in an even more mind-boggling variety of properties and uses. Without them, we would very possibly still be in the Stone Age.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |