| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of a medieval cathedral wall with panels of illustration}

1 Caption: Making webcomics

|

First (1) | Previous (3200) | Next (3202) || Latest Rerun (2888) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3201.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

A question I've been asked a lot over the past nine years is: "Can you give me some advice on making my own webcomic?" I've typed out various answers into many e-mails and I figured it would make sense to compile some of that into a single spot. So here goes.

Not that sort of web... |

Okay, fine, but what's a comic? Various more or less learned people have debated over the precise definition, but it's loosely a form of storytelling that is told through a medium of visual artwork, which may or may not be captioned with text. Getting too precise about definitions is a problem in many fields, because you run the risk of including stuff you didn't mean to include, and/or cutting off some stuff that you wanted to include. Early in the run of Irregular Webcomic! I tried to enter it into an online competition for webcomics, and was told I couldn't participate because IWC was made with photos and therefore wasn't a "real" comic. Since then, comics like A Softer World have won webcomic awards, so I think it's fair to say that the zeitgeist definition of what makes a comic has expanded a bit.

Ten years ago, if you went looking for advice on how to make comics, the only resources you would have been able to find were books that started by telling you what kind of paper, pencils, and ink to get. Since then, there's been an explosion in the number of comics produced without using any of those traditional tools. Furthermore, I'm not particularly talented with or knowledgeable about drawing implements, so I'm not about to start offering advice about those.

These days there are plenty of other ways to make your visual artwork. You can still make it in the traditional ways, of course, and if you're talented or keen there's little I can tell you about that (the major hurdle remaining is getting your artwork online - read on). You can also create original art entirely digitally, using various painting or drawing programs, though this still requires artistic skill. Another option for prospective comic writers is to collaborate with an artist. This is the way many classic comics of the past worked, with the writer and the artist being different people. Finding an artist to work with (or if you're an artist, finding a writer) can be tricky, but the net has made it somewhat easier. Any of various social networking sites or forums will connect you with an audience of people who might be interested in a creative collaboration. There are risks with working with someone you don't know, of course, but you can always try and start again if things don't work out.

Comic made from photos assembled in Comic Life. |

Well, firstly photography is an art form - and maybe I'll say more about that in a future annotation. Secondly, the planning and effort that goes into some photo comics' photography is substantial. Many brick comic creators, for example, spend hours blocking out scripts, designing sets, building sets, and arranging scenes and lighting to get those "easy, lazy" photos. (I'll admit that I didn't always do this, especially in recent years, as I was indeed getting lazier and more pressed for time, but that's no reason to tar all photo comic artists with the same brush.) I do have some tips for making good comic photos, but I'll get to those in a minute.

The essential bit about making comics is combining the artwork into a story. Traditionally done right on the drawing board, this is increasingly a job for the computer. Using a graphics program makes laying out panels and adding captions something you can play around with dynamically. Some programs, like Comic Life, are designed specifically for laying out and captioning comics, which makes it easy for beginners to start. General purpose programs like Adobe Photoshop and the GIMP give more flexibility, at the cost of a steeper learning curve. If you already use a general graphics editor, stick to what you know, otherwise a comic creation program can be a good way to get started.

Composition and layout is where things get tricky. To successfully lay out a comic strip—both the layout of the panels with respect to one another and the composition of the artwork within the panels—you need a good sense of visual design and knowledge of the conventions of comic layout. A good reference here is Scott McCloud's seminal book, Understanding Comics. Basically, if you're trying to make comics, and you haven't read this book, you're making life much harder for yourself. If you're thinking about making comics, buy this book. You'll thank me for it.

You can (and should) also pick up this design stuff by studying successful comic layouts, from many different styles and creators. I recommend familiarity with a good number of daily gag strips, traditional superhero comic books, Japanese-style manga, and European comic books. All of these offer different perspectives and techniques, and it pays to know as many as you can. For the latter, a study of Herge's Tintin comics is pretty much an essential; in fact I shudder to think of anyone trying to design a comic strip without being familiar with Herge's style. I'll also recommend Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen by name, but there are dozens of other influential and very good comics out there.

Writing your comic is the next part. Probably the most important thing I've learnt about writing comics is that less is more. Brevity is good. Keep the text as minimal as you can. After writing a script for a comic, you should reread it, and trim away as many words as you can while still conveying your message. Then repeat the process, a few days later. And when composing and laying out your artwork and adding the dialogue, see if you can trim it down again.

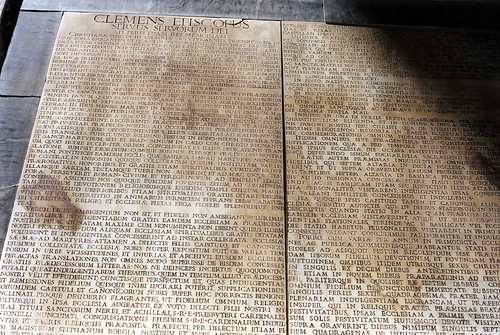

A wall of text. |

I find that once I've written something, I can usually go back and trim 30-50% of the text away without losing any of the meaning. You must do this to your comics. Unless you are writing a character who is deliberately verbose, you should always aim to use as few words as possible. A wall of text that could have delivered the same message in half the space is a turn off[1].

The next step is to create your artwork. The only art form I can give tips on here is photography. If you're illustrating your comic with photos, you need to take decent photos. Learn something about photography - it'll also help when you want to take snapshots or holiday pictures. Think about the composition of the photos and the backgrounds. Don't just put the speaking characters into a frame or you end up with a "talking heads" comic that could just as well have been done as stick figures. Think about ways to show motion and dynamism, which are tricky things to convey in a photo.

On the technical side, make sure your photos are in focus and free of motion blur (unless you want motion blur). Use a tripod if you have to. I've seen plenty of attempts at photo comics that have been marred by blurry photos. If you're shooting small sets from close up, make sure your camera can focus that close - not all of them can. You may need to engage a macro mode to do so. Read your camera's manual and know how to use it. And if you're photographing LEGO (and why not?), visit the friendly people at the Brick Comic Network forums for tips and encouragement.

And while on cameras, the best camera for shooting small scale models is actually an inexpensive compact camera, not a fancy DSLR. The sensor size and wide aperture of an SLR combine to create very shallow depth of field at macro scales, making focus difficult and rendering backgrounds very blurry. The wider depth of field of a compact camera gives you more latitude and the ability to see some detail in the background, although you do want some focus difference to highlight your foreground characters. I have an EOS 5D Mark II which I use for travel photography, portraits, weddings, etc. I have an IXUS 75 which I used for photographing comics in the last 4 years, and before that I used a Coolpix 4300.

Lighting a model for photographing is more difficult than it seems, and should not be neglected. It's easy to create harsh shadows that detract from the models. Ideally you want soft ambient light with a little bit of highlighting. To do this effectively, it's best to have multiple light sources that you can position more or less arbitrarily, such as desk lamps. To avoid harsh shadows, the lights should be diffused by placing something translucent in front of them (paper works, but be careful not to set it on fire if your lights are hot, or there are special heat-resistant diffusing sheets you can buy from photographic suppliers) or by bouncing them off a white wall or piece of card. Some understanding of the field of movie set or portrait studio lighting is good, especially things like three- and four-point lighting.

Once you have artwork and script assembled into comics, you need a place to show them off. If you have web coding skills, you can make your own website. If not, either enlist a friend who does (and compensate them for their time and effort - it's more work than you might think), or look to a site that offers ready made hosting suitable for displaying comics. Some people simply post comics to Facebook or DeviantArt. There are also dedicated comic sites such as Comic Genesis, Smack Jeeves, or The Duck (formerly Drunk Duck).

In fact, while listing sites, there's a neat list of webcomic resources at TV Tropes (don't worry, this link by itself won't get you lost in TV Tropes. Well, unless your willpower is exceptionally weak).

Don't expect to make any. |

Don't start a webcomic expecting to make any money. Do it because you want to make comics and will do it even if it takes you time and effort for no reward whatsoever.

More importantly, don't expect everyone to love your work. The Internet is a harsh critic. You will get people saying your comic stinks. You will get people writing detailed explanations of exactly why your comic stinks. You need to be able to ignore them and just keep going. You may also get people who like what you do. You need to be able to accept that gracefully and not get a big head.

Thirdly, and most importantly of all, decide how often you are going to update your comic and stick to your advertised update schedule. Nothing, and I mean nothing, will lose you readers faster than missing your update schedule. Your comic can be mediocre or even bad, but if you stick to a regular update schedule like clockwork, you will retain more readers than a great comic that promises regular updates and fails to deliver. And you won't be able to help getting better at it. Be realistic about what you can sustain over the long term. It's no use starting with a daily comic and then getting 3 weeks into it and realising you can't keep up the production rate. It's better to advertise 2 or 3 updates a week, maintain a buffer of strips, and release them on time, without fail. If you find you can make them faster than you publish them you can always increase your publication rate later.

I hope this has provided a few people with some useful tips, and the rest of you with some insight into how I approach making my own comics.

[2] Contrary to the now common saying that "rules are meant to be broken" or the commonly touted wisdom that you can break the rules if you know what you're doing, this mainly only applies to rules of thumb, not all rules. And particularly not rules such as "no cheating in exams" or "kitchen staff must wash hands after using the bathroom".

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |