| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

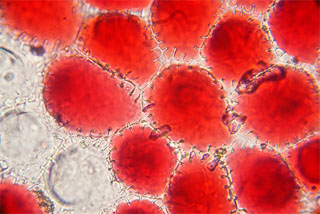

1 {photo of plant cells magnified under a microscope}

1 Caption: Bricks of Life

|

First (1) | Previous (3236) | Next (3238) || Latest Rerun (2890) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3237.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Diagram of a typical animal cell. Some of these components are not described in today's annotation. (1) Nucleolus (2) Nucleus (3) Ribosomes (small red dots) (4) Vesicle (5) Rough endoplasmic reticulum (6) Golgi apparatus (7) Cytoskeleton (8) Smooth endoplasmic reticulum (9) Mitochondria (10) Vacuole (11) Cytosol (12) Lysosome (13) Centrioles within Centrosome Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike image by MesserWoland from Wikimedia Commons. |

Cells are tiny components that come in many different types and shapes, that perform different jobs, and that fit together to build up the bodies of living things. Kind of like LEGO bricks. Most individual cells are far too small to see, except through a microscope (though some are large enough to see easily, as we'll see in a little while). The tip of your little finger, from the last knuckle to the end, is made up of roughly a billion (109) cells, and your whole body about 10,000 times that many, for a total of around ten trillion (1013) cells.

Most of those cells are alive, in the sense that they take in nutrients, process them, excrete waste products, and can reproduce. Some of them, such as the ones making up the external layers of your skin, are dead, in the sense that they no longer do these things, but they still perform useful functions for your body.

Each cell is a variation on a single basic structure. A cell is a small blob of fluid enclosed by a thin membrane, sort of like a water balloon. The fluid is called the cytoplasm, and the membrane is called, funnily enough, the cell membrane. The cytoplasm isn't just water; it's thick and soupy with chemicals, and it also contains more solid structures within it. Some of the chemicals are simple atomic ions, for example potassium atoms with an electron stripped off. Some are more complex molecules than we've discussed before, massive behemoths of hundreds of atoms, and we call such molecules proteins. And other molecules that are much more massive still, but we'll get to those later.

Inside this mix of cytoplasm are various structures that perform different jobs. Threads of protein molecules form a loose structural skeleton, the cytoskeleton, giving the cell some shape and stability. Other structures form blobs of various shapes and sizes within the cell, acting as mini "organs" for the cell, a role that is reflected in their collective name: organelles.

A simple organelle is the vacuole, which is mostly a storage facility, like a smaller water balloon within the overall cell, but filled with chemically different material. Vacuoles perform a range of jobs, such as: simply storing water for use by the rest of the cell; storing certain proteins used by the cell; storing waste products so they don't pollute the rest of the cell; surrounding potentially dangerous foreign matter to isolate it from the rest of the cell; transporting all of these materials around the cell to places where they can either be used or expelled; and maintaining the internal pressure of the cell. This last job is especially important for plant cells, to give the plants some of their structure and rigidity, and plant vacuoles are large. When you bite into an apple or orange, the juiciness is released from the cell vacuoles. The orange cells are so large that you can see the individual cells - yes, each one of those little sausage-like bubbles that bursts with juicy goodness is a single cell, consisting mostly of one very large vacuole filled with the sugary liquid we know as orange juice.

Red geranium petal cells. Creative Commons Attribution image by Umberto Salvagnin, from Flickr. |

The protein molecules that the Golgi apparatus works with are produced in another organelle called the endoplasmic reticulum. This is a somewhat similar looking folded structure with many layers and tubes. If the Golgi apparatus is the shipping department, the endoplasmic reticulum is the factory floor, where smaller molecules are assembled into proteins and bits of membranes that then get sent out to other parts of the cell. This is done in smaller structures within the reticulum, known as ribosomes. Ribosomes are sort of like the assembly lines of the cell factory. There are different types of endoplasmic reticulum, with different roles, one type also metabolises food to supply energy - the power generation for the factory.

The data centre for the cell is in the organelle known as the nucleus. The nucleus contains the genetic information of the cell, encoded on very large molecules called deoxyribonucleic acids, or DNA. There's lots to be said about DNA and how it works, but for now let's just consider it to be the storage medium in which all of the instructions for running the cell are kept. The nucleus makes copies of parts of this information and passes it out to the endoplasmic reticulum. The information is essentially recipes for making different sorts of proteins, and the reticulum uses the recipes to assemble the required proteins out of other, smaller molecules.

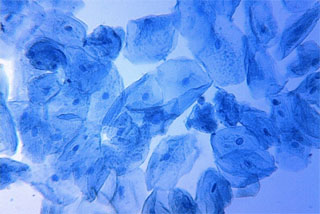

Human cheek cells. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike image by Joseph Elsbernd, from Flickr. |

Getting back to the nucleus, it also controls reproduction of the cell. This process begins with the separation of the DNA into discrete strands known as chromosomes. The chromosomes divide into two, replicating the DNA data by assembling copies from the surrounding supply of smaller molecules. (There's lots of detail in this process, again a story for another day.) The nucleus then splits into two, each one carrying a full copy of the cell's DNA. The whole cell then splits in two, each half carrying one of the new nuclei. And so one cell becomes two more or less identical copies of itself.

The division of cells happens millions of times each day in your body. The process allows living beings to grow and to replace cells that die. Unfortunately, it's a complicated process that can sometimes go wrong. If the DNA data gets corrupted it can cause the cell division process to occur too frequently, resulting in abnormal growth of tissue. In animals, this causes several problems, the most serious being the disease we know as cancer. Cancer is very difficult to fight because, apart from their abnormal growth pattern, the cancerous cells are very similar to normal cells of your own body. There is very little difference for treatments to latch onto and allow them to destroy cancerous cells without also destroying normal body cells.

Bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells (false colour). Creative Commons Attribution image by Joseph Elsbernd, from Flickr. |

Getting back into the details of cells, there's another way they can come to harm. The cell membrane generally keeps the insides of the cell in, and the outside out, but it has to be porous to materials such as nutrients coming in, and waste products going out. It achieves this by having pores, essentially holes the size of molecules, but guarded by clumps of molecules that interact with any potential ion or molecule that approaches. The gatekeeper molecules allow certain things through, but keep others from passing. Normally this process works fine, but it can be disrupted by certain foreign molecules. There are molecules that, if introduced into your body, have parts that mimic things the pore gatekeepers want to let in, but attached to those parts are clumps of other atoms that block up the pore. The result is that the cellular pores get blocked, and the cell can no longer function properly. These foreign substances we call toxins, and the sort of toxins that work this way are usually organic things like snake or spider venom, or the toxins produced by certain frogs, fungi, and plants. Other classes of things that are bad for you if they get inside your body, such as arsenic or bleach, work in different ways, and are generally called poisons, not toxins.

When things aren't going wrong, though, cells do a great job of making all of the components of your body. They come in different shapes and sizes, and perform very different jobs. The cells in your muscles are flexible and stretchy, and at a signal from your nervous system they contract, pulling like brake cables to move various parts of your body around. Your nervous system is made of cells specialised to carry electrical signals around your body. Your liver and kidney cells perform filtering functions, collecting and sorting out the waste products of all your other cells so they can be broken down or excreted from your body. Cells travel in your bloodstream: white cells that patrol looking for hostile organisms, and red cells that carry oxygen from your lungs to everywhere else in your body, to power all the other cells there.

There's heaps more to say about cells and how they work. There's even a major organelle of animal cells that I haven't even mentioned yet... But I'm a bit pressed for time this week, so further exploration of the building blocks of life will come later.

Title image is a photo of magnolia petal cells. Creative Commons Attribution image by Umberto Salvagnin, from Flickr.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |