| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of a human silhouetted against the sun}

1 Caption: The Sun's Energy

|

First (1) | Previous (3252) | Next (3254) || Latest Rerun (2895) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3253.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

A chemical reaction: combustion. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike image by David Lindes. |

These were great principles, and allowed us to figure out all sorts of marvellous discoveries about the natural world. But a few niggling things still hovered tantalisingly beyond our comprehension. One problem in particular seemed a bit esoteric to most people, but was a major concern across all fields of science: what made stars shine? Stars emit a lot of energy in the form of light, heat, and other electromagnetic radiation. Where does it come from?

In 1900, the best answer anyone had was that the energy came from a gradual contraction of the star under gravity, which would reduce the gravitational potential energy of the star. The problem was we knew the sizes and masses of stars, and how much energy they produced, and if you run the numbers, gravitational contraction only has enough energy to supply a star like our sun for a few million years.

But this was at a time when the fields of biology and geology were both piling up evidence that the Earth must be hundreds of millions of years old, if not thousands of millions (i.e. billions, in the American counting system). Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection was quickly gaining favour, and it required many millions of years to produce the diversity of life in evidence all around us. And the evidence from rock formations all over the world pointed to hundreds of millions of years being necessary to explain them. But the only theory we had for the age of our sun pointed to an age of about 10 million years, maximum. Something was wrong.

A speeding train. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike image by Doug van Kampen. |

Time dilation is not the only weird effect of special relativity. Relative motion not only affects time, it also affects distance. The effect is called length contraction. As objects move, they get shorter. Their length, measured in the direction of motion, shrinks or contracts. To give a concrete example, let's use a train again. Suppose you're standing still on a platform, and a train is rushing past. If you measure the length of the moving train, you would find that it is shorter than the length of the train when it is standing still. We need to be a little careful when we say "measure the length of the moving train" here. Set up a long ruler beside the track and have people stand at either end, roughly where the ends of the train will be, with synchronised clocks. As the train rushes past, at an agreed tick of the clocks each person marks on the ruler precisely where their end of the moving train is at that moment. The distance between the marks is the length of the moving train. And if you compare it to the length of the train measured when it's standing still, you'll find the length of the moving train is shorter.

There are a couple of details here. Obviously this is an inefficient way to measure the length of something moving past at high speed, and prone to errors if you were to try it in real life. But conceptually you can see that if the people were really precise and could accurately pinpoint the location of the ends of the train at a given time down to tiny, tiny fractions of a second, it should work. The second point is that this change in the length of the train is not caused by any bunching up of the carriages due to slack at the couplings or anything like that. If it helps, imagine it's a bus, a single box made of metal. The change isn't caused by elasticity either, as though the train/bus was a spring that wobbles and gets shorter as you push it from behind.

Measuring length. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike image by Chandra Marsono. |

As with all effects of relativity, length contraction only really becomes noticeable at speeds close to c. So we don't see it in our everyday lives, which makes it completely outside the realm of experience and common sense. But it's real and there are experiments that demonstrate it. When subatomic particles interact, the outcomes depend on the density of charge and matter. When a particle is fired at close to the speed of light, in a particle accelerator like the Large Hadron Collider, length contraction squishes it so its shape is more like a discus than a sphere, flattened in the direction of travel. This flattening changes the particle's charge and mass density. To correctly predict the interaction strength as it collides with a target, you have to use this relativistically compressed density.

This touches on a third effect of travelling close to c - the effect on mass. Mass and speed combine to give kinetic energy, the energy of motion. And here is where Einstein made the astonishing discovery that became synonymous with his name. When deriving the kinetic energy and momentum of an object moving at speeds close to light, he found that the energy and momentum both ballooned quickly, tending towards an infinite value as the speed got ever closer to c. Einstein considered how energy and momentum are transferred between particles in collisions, and concluded that things made more sense if the total energy of a moving object was equal to its kinetic energy plus another term that was equal to the particle's mass times the square of the speed of light.

Truck on a portable weighbridge. Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike image by Wikipedia user Mostin89. |

E = mc2

Energy equals (relativistic) mass times the square of the speed of light.

If Einstein's initial interpretation is correct, then going back to our train again, if there was a section of track set up to weigh the train (like a truck weighbridge), we could weigh the train as it stood still. But if the train was moving along the tracks, and the bridge could weigh the train accurately as it moved (in the fraction of a second that it was squarely on the bridge), we'd find the weight reading was bigger. Again, as with time dilation and length contraction, this effect is so tiny as to not be noticeable unless the speed involved is close to the speed of light.

However, Einstein later expressed uncertainty on this particular point, and said that it was better to avoid the concept of relativistic mass and simply concentrate on the relativistic expressions for energy and momentum. Other physicists now argue that although Einstein's expressions for the energy and momentum of objects moving at high speeds are correct and—when compared to the expressions for kinetic energy and momentum in Newtonian physics—imply that the mass of the object has increased, they should not be interpreted as the mass of the object actually changing. Rather than the additional increase in energy and momentum (over Newtonian physics) coming from additional mass, it originates in the interactions of space and time.

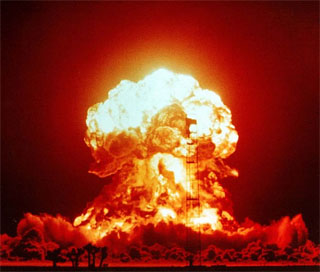

A nuclear explosion. The BADGER explosion on April 18, 1953, Nevada Test Site. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

And, as Einstein pointed out, the most astonishing of those consequences is that idea that mass is actually equivalent to energy. Like kinetic energy, and gravitational potential energy, and chemical energy stored in chemical bonds, mass is a form of energy.

Going back to the two principles we began with, conservation of mass and conservation of energy, we can now reformulate them into a single principle: Conservation of mass/energy. It's essentially the conservation of energy, just recognising that mass is actually one form of energy. Thinking about this, this implies that you can convert mass into other forms of energy, or vice versa, convert other forms of energy into mass. And the conversion rate is c2, which is an enormous number. Mass is equivalent to absolutely humongous gobs of energy.

And suddenly, without even thinking about applications to astrophysics, Einstein had found the answer to what makes stars shine. Or rather, he'd found the scientific principle which can allow a star to generate enough energy to shine for billions of years. If a star can convert some of its mass directly into energy, that would easily provide more than enough energy. It took a few more years for astrophysicists to iron out the details. In 1920, Arthur Eddington used very precise measurements of the atomic masses of hydrogen and helium (made by others) to show that it was feasible that the sun could produce its energy entirely by converting hydrogen into helium in nuclear fusion reactions. In 1939, Hans Bethe published details of the exact reaction chain that would allow this to happen.

If there's any consequence of Einstein's relativity that is established beyond any shadow of a doubt, it is the equivalence of mass and energy. This is the principle that allows stars to shine. It explains radioactive decay. It explains nuclear reactions in general. It allowed the building of nuclear reactors, and nuclear weapons. If relativity was wrong, these things wouldn't work.

On the other hand, if relativity was wrong, our sun wouldn't be shining, and you and I wouldn't be here.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |