| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of Saturn}

1 Caption: The Ringed Planet

|

First (1) | Previous (3274) | Next (3276) || Latest Rerun (2873) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3275.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Christiaan Huygens. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

Like the other five planets (and the moon and sun), we have inherited a day of the week named after its associated god: Saturday. Saturn was also associated with another time: the Roman festival of Saturnalia. Saturnalia was an end of year celebration marked by a playful overthrow of the normal rules and conventions of Roman civilisation. It involved feasting, gift-giving, and reversal of societal roles, with masters serving their slaves. All of these customs still take place at the same time of year in modern western civilisation, now associated with the occasions of Christmas and Boxing Day (though the role reversal has become much more limited in the last century or two).

Saturn has also given us an adjective: saturnine. Its meaning relates to Saturn's ponderous movements across the sky. A saturnine person is dull, gloomy, and melancholy.

The reason Saturn is so slow in crossing the field of stars is that it is the furthest away of the classical planets. As Johannes Kepler first published in his Third Law of Planetary Motion in 1619, the time it takes a planet to move around the sun increases as the 3/2 power of the size of the orbit. Saturn, at almost twice the distance of Jupiter from the sun, takes two and a half times longer to complete one orbit. Whereas Jupiter cycles around its orbit in under 12 years, Saturn takes almost 30.

Saturn's best known feature was first observed by Galileo with his telescope in 1610. Having seen that Jupiter was accompanied by four moons, he found something much stranger when he looked at Saturn. There seemed to be projections sticking out from either side of the otherwise round planet. Galileo likened them to "ears". He had no idea what they were.

Giovanni Cassini. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

Fascinated by the planet, Giovanni Cassini devoted much of his research to Saturn. His telescope was good enough to let him discern some structure in the ring, most notably a gap, splitting it into two separate, concentric rings. The gap is still known as the Cassini Division. What the rings were, or what they were made of, however, remains a mystery for another 200 years.

James Clerk Maxwell, the man who laid out the mathematical foundations of electromagnetism, also applied his mathematical skills to the dynamics of the rings. By applying Newton's law of gravity and an understanding of the strength of material objects, Maxwell concluded that the rings could not be solid objects. The gravitational forces at that distance from Saturn would tear apart a continuous ring made of solid matter. He proposed instead in 1859 that the rings were formed of many small fragments, each one individually orbiting Saturn like a tiny moon.

Meanwhile, the known structure of the rings had been growing in complexity. in 1837, Johann Encke noticed that the ring outside Cassini's division was not uniform in brightness, but showed some variation across its radius. Then in 1850, William Bond and his son George were the first to observe a third broad ring. It was fainter and inside the two brighter rings that framed the Cassini Division. It has since become known as the C Ring, after the ring outside the Cassini Division was named the A Ring, and the ring inside the Cassini Division was named the B Ring.

Later in the 19th century, James Keeler made extensive observations of Saturn's rings. In 1888, he found that the A Ring itself contained a gap, smaller than the Cassini Division but just as distinct. This was named the Encke Gap in honour of Encke's earlier observations. Keeler made an even greater discovery in 1895, when he aimed a spectroscope at Saturn's rings using the Allegheny Observatory telescope.

Saturn's rings, showing the bright B and A Rings separated by Cassini's Division. The faint C Ring can be seen inside the B Ring. Public domain image by NASA/ESA from Wikimedia Commons. |

Photographic observations in the 1960s teased out two more faint rings, the thin D Ring inside the C Ring, and the very broad and faint E Ring which covers a huge area outside the A Ring. Further discoveries came with the flybys of the deep space probes Pioneer 11 in 1979, Voyager 1 in 1980, and Voyager 2 in 1981. Pioneer 11 discovered another distinct ring, the thin F Ring, outside the A Ring. The Voyagers sent back the first high-resolution images of the ring system, and in doing so exploded our knowledge of the rings.

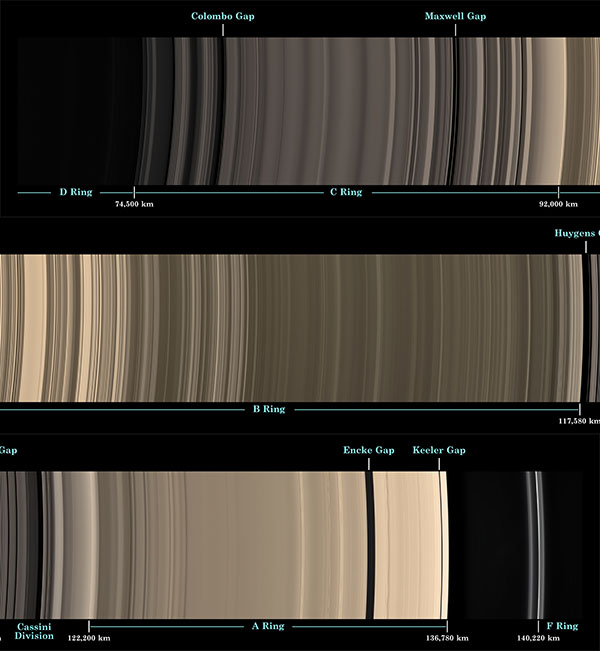

Detailed structure of Saturn's rings. (Cut into 3 to fit this page. See here for large version.) Public domain image by NASA from Wikimedia Commons. |

The rings contained vastly more structure than anyone had imagined. Apparently continuous from Earth, when seen from close up each of the known rings split into thousands of thin rings of varying thickness and brightness. The structure changed for every few kilometres of radial distance from Saturn. Voyager also revealed what caused this incredibly complicated structure. Orbiting amongst and between the rings were dozens of tiny moons, on the order of tens of kilometres in diameter. Large moons would be broken up by the tidal forces of Saturn this close to the planet; this is what keeps the ring particles from coalescing into a moon. But for tiny moons the tidal forces are small enough that their structural integrity allows them to survive. (In fact the ring particles themselves are really billions of tiny moons, from dust particles up to a few metres across.)

What this army of tiny moons does is to cause gravitational perturbations in the ring environment around Saturn. The little nudges provided by the moons push the ring particles into distinct regions and away from other regions.[1] This causes the pattern of gaps and dense ring regions at various orbital distances from the planet. The sharp edges seen at places like the Cassini Division and Encke Gap are caused by moons orbiting just outside the ring, pushing the ring particles away from the gap region.

These so-called shepherd moons not only confine the ring particles into detailed concentric patterns, they produce ripples and other effects that move the ring particles up and down, away from the orbital plane. The thin F Ring turned out to have a moon immediately on either side: Prometheus on the inside and Pandora on the outside. As they orbit Saturn, each of the moons pulls material from the F Ring towards itself. But as one moon passes, the next moon is on the way, and pulls the material back in the other direction. Prometheus and Pandora are both highly irregularly shaped, being too small to form spheres. The asymmetries in the system result in the F Ring material being pushed up and down as well as in and out. As a result, the F Ring turned out to be the most complex dynamical system discovered anywhere in the solar system. It actually consists of a central, almost circular ring, surrounded by particles that form another ring spiralling around the central ring.

Ripples in the rings in the wake of the moon Daphnis, which orbits in the Keeler Gap. Shadows are cast by the ripples on the rings. Public domain image by NASA from Wikimedia Commons. |

But the strangest phenomenon discovered by Voyager were radial shadows on the rings. The science team called them "spokes" because they resembled bicycle wheel spokes. They rotated around the planet, staying stable for several rotations. If you remember Kepler's Third Law, it becomes clear that these features cannot be directly associated with the separately orbiting ring particles, as they move at different speeds and will get out of synch very quickly. For a while there was no known physical explanation for these mysterious shadows. The answer came when Carolyn Porco realised that the spokes were rotating at the same speed as Saturn itself. They were not tied to the ring particles, but to the planet. The only thing that far away from Saturn that would rotate at the same speed as Saturn was the planet's magnetic field. Porco made the connection and realised that the spokes are caused by magnetised dust particles, tracking the passage of Saturn's magnetic field as it sweeps through the rings. Porco said of this moment, "I'll never forget when I realised there was this connection - it was tremendous to know something that no one else on the planet knew."

Infrared image of the surface of Titan taken by Cassini. Public domain image by NASA from Wikimedia Commons. |

From Earth, Titan is an obscured ball, much like Venus, smothered in clouds. The moon was discovered by Christiaan Huygens in 1655, the same year in which he resolved Galileo's "ears" into the rings of Saturn. It was the next moon in our solar system to be discovered after Galileo observed the four main moons of Jupiter. In 1944, Gerard Kuiper concluded from observations of the moon that it had an atmosphere containing methane. In 1980, Voyager 1 passed close to Titan, specifically to capture close up images of the moon. Unfortunately, the atmospheric haze foiled this attempt. The Voyager 1 images of Titan show only a featureless ball. Given this, the Voyager 2 mission the following year was modified to concentrate on Saturn's ring and other moons. It barely looked at Titan at all.

Later, spectroscopic observations from Earth teased out some of the atmospheric constituents of Titan. Planetary scientists realised that given the atmosphere of nitrogen, methane, and other hydrocarbons, combined with the temperature of the moon, Titan could contain surface features consisting of frozen and liquid hydrocarbons, and possibly a weather cycle involving rain and evaporation of liquid methane. With an atmospheric pressure equal to 1.4 times that of Earth, making it the closest atmospheric pressure to Earth anywhere in the solar system, it seemed Titan might be a very interesting place indeed. We needed to know more about Titan.

NASA joined forces with the European Space Agency and Italian Space Agency to work on a combined deep space probe mission to Saturn and Titan. The mission was named for the two astronomers most historically connected with Saturn: the Cassini-Huygens mission. In 1990, The leader of the science imaging team for Cassini-Huygens was chosen: Carolyn Porco. The probe took almost a decade to design and build, and it was launched in 1997. In 1999, on the BBC Planets documentary, Porco expressed how difficult it was to have to wait until Cassini-Huygens arrived at Saturn in 2004. The sense of expectation and excitement, of new discoveries just around the corner, was palpable in that television program.

Carolyn Porco. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike image by Eirik Solheim from Wikimedia Commons. |

Cassini is also equipped with radar to allow imaging of the surface of Titan through the clouds. This has revealed a topography and geology of the moon reminiscent of many features seen on Earth: mountains, lakes, rivers, and even sand dunes. As of this writing, Cassini is still in orbit and returning new science data on Saturn, its rings, and Titan. It has revealed that the large lakes on Titan, composed of liquid ethane and methane, are stable over several years. Cassini has also supplied Porco and her team with mountains of new data on Saturn, several newly discovered moons, more details of the ring system and its dynamics, and detailed data on the moon Enceladus, including the discovery of geysers and cryovolcanoes on the moon. Even Saturn itself is revealing new secrets, with detailed observations of storm systems in its atmosphere.

Cassini is now on a death spiral, with its current orbit designed to decay to the point where it will collide with Saturn's atmosphere in 2017. Until then it should continue to provide further observations. The collision itself will also provide an important science opportunity as it stirs up the gases in the planet's atmosphere.

I hope to read about Carolyn Porco's observations and discoveries about Saturn for several years to come.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |