| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of a cathedral under a deep blue sky}

1 Caption: Polarisation

|

First (1) | Previous (3334) | Next (3336) || Latest Rerun (2895) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3335.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Michael Faraday, photographed in 1913. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

Anyway, Tyson's remake has the advantage of new discoveries made since 1980, and more advanced visual effects. Nevertheless, I get the slight nagging feeling that Tyson's script is talking down to the audience a little bit - a feeling I never got with Sagan (and I rewatched Sagan's Cosmos just a few months ago and didn't feel it then). And I got it especially with the latest new episode I watched, which was about electromagnetism and Michael Faraday.[1] Tyson was narrating an experiment which Faraday had performed with polarised light, to see if a magnetic field would affect it. I thought his explanation of polarisation was, well, sloppy and not very informative. What's more, he followed up with a pseudo-apology, saying (paraphrased slightly - I don't recall the exact words), "Don't worry if you didn't quite understand that, it's pretty complicated."

This is the wrong thing to say in an educational program!! I was practically screaming at the TV (not literally, since my wife was watching with me), "I could have written that bit better! You have four sentences to explain polarisation, and that's the best you can do?!"

Now, it is very easy to criticise something for being less than perfect, or even just less than you think it should be. Everyone criticises stuff - just take a look at the Internet any time. What's more difficult, and what most criticisers fail to do, is to do better. Very well, Tyson. Thou hast thrown down the gauntlet, and I hereby pick it up:

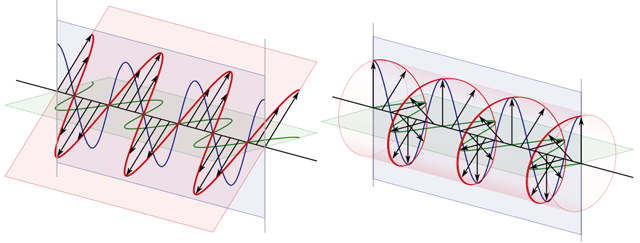

Light is an electromagnetic wave, which is to say a propagating wave made of electric and magnetic fields. The electric field, to pick one, can oscillate in any direction perpendicular to the direction the light is travelling, in the same way that a stretched string can vibrate up and down, or side to side, or any angle in between. Normally, light is made up of collections of waves oscillating in all directions, or polarisations, randomly. But it's also possible to generate or filter light so that it is made up of waves all oscillating in the same direction, or polarisation - and we call that polarised light.

There's a lot more you can say about polarisation and polarised light, but those few sentences would have introduced the concept and explained it enough for viewers to understand Faraday's experiment much better.

Light waves commonly have electric fields oscillating in all directions (left). Passing through a polarising filter (grid at centre) restricts the transmitted light's electric field to a single plane of oscillation (right). Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike image by Bob Mellish, from Wikimedia Commons. |

Much of the light in the natural world is comprised of a random mixture of all polarisations, making what we call unpolarised light. But certain processes can filter out some polarisations, leaving others to continue as more or less polarised light. Polarisation is not an all or nothing thing. If a beam of light is predominantly polarised in one direction, but still contains some light polarised in other directions, we say the beam is partially polarised. The degree of polarisation can be anything from 0 (completely random and unpolarised) to 100% (all light in the beam is polarised in exactly the same direction).

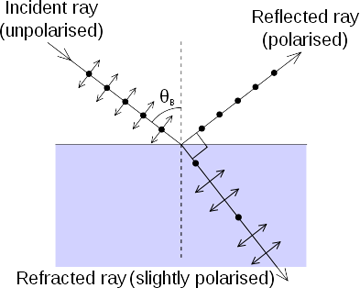

How is polarised light generated? One simple way, which occurs in nature, is to reflect it off something transparent, say a sheet of glass or pool of water. When light hits the surface of a pool of water, some of the light passes into the water, but some is reflected off the surface. Which specific waves of light pass through and which are reflected depend strongly on their polarisations. At a certain specific angle of incidence (which is governed by the refractive index of the material), all of the reflected light will be polarised, with its electric field oscillating parallel to the water surface. All electric field oscillations perpendicular to the surface pass into the water.

This separation of light into different polarisations does not just pick out the tiny tiny fraction of light rays (or photons, if you prefer) which happen to have polarisation parallel to the water surface, and reject all the others. That would leave very little light at all, since almost all of the light is not polarised exactly parallel to the water surface. Rather, the reflection separates all of the light into components parallel and perpendicular to the surface. So if the light already happens to be fully polarised at, say, 45° to the surface, then half the light is reflected and half the light passes into the water.

Light incident on a surface at the Brewster angle. Most of the polarisation parallel to the surface (dots) is reflected, none of the polarisation perpendicular to the surface (arrows) is reflected. Public domain image by Wikipedia user Pajs, from Wikimedia Commons. |

One wrinkle in this method of polarising light is that the light only becomes fully polarised if it is hitting the water at the specific angle previously mentioned. This specific angle is called the Brewster angle. At other angles, the reflected light is only partially polarised, with the amount of polarisation decreasing as the angle moves away from the Brewster angle.

Another way to produce polarised light is to pass it through a polarising material. One such material is known by the trade name of Polaroid[2], and is commonly used in sunglasses and glare filters. Polaroid works because of its molecular structure. During manufacture, the plastic material is stretched in one direction. This lines up long polymer molecules, forming sort of spaghetti strands within the material, all parallel to one another. These strands have electrical properties that affect the passage of light. An electric field oscillating perpendicular to the strands can pass through, but not one oscillating parallel to them. This means that if light passes through a piece of Polaroid, only the electric vector components perpendicular to the molecules can get through. The component of the field parallel to the strands is blocked, and the Polaroid material absorbs that energy. If you shine a beam of unpolarised light through Polaroid, the light that emerges is polarised in one direction and has energy (or intensity) half that of the incoming light. The other half is absorbed. This is why Polaroid material looks a dark grey colour - it is blocking half the light that enters it.

Polarising sunglasses. Reflected glare from the road is greatly reduced. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike image by Ed Flores, from Flickr. |

This effect of reducing typical glare only works if the Polaroid molecules are aligned horizontally. If the Polaroid is rotated (you can try this if you have polarising sunglasses by simply turning them, or tilting your head while wearing them), it won't be as effective at cutting the reflected glare. Polarising sunglasses won't normally reduce glare reflected sideways off vertical panes of glass, but they will if you turn them by 90°.

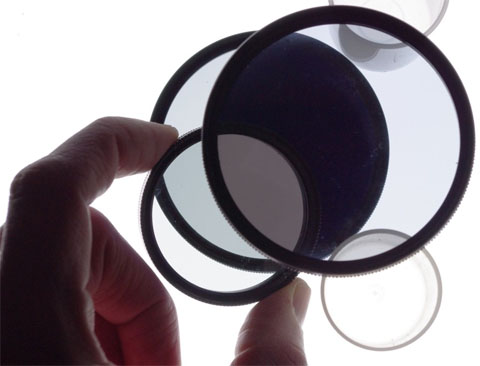

Here's where polarised light starts getting really interesting. If you take two pieces of Polaroid and hold them up together, you can see some interesting things. Each piece of Polaroid cuts the brightness of normal unpolarised light by 50%. So if you stack two of them on top of each other and look through them, how bright is the light passing through? The answer is: it depends. If the molecular axes of the two pieces of Polaroid are aligned, then the light hitting the second sheet is already polarised by the first sheet, so all of it passes through and none is absorbed. On the other hand, if the molecular axes are at 90° to one another, all of the light is absorbed by the second sheet and none gets through. So depending on the relative rotations of the two sheets of Polaroid, the resulting brightness can be anywhere from 50% to 0% of the original light. If you have two pairs of polarising sunglasses you can see this effect easily by looking through both pairs at once, and rotating one of them.

Stacked linear polarising filters. The two large filters are at 90°, so they block all light. The smaller filter is turned to an intermediate angle, so passes a component of the light from the first filter at that angle, which then provides a component which can get through the second large filter. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial image by Paul, from Flickr. |

The angle by which the plastic rotates the polarisation depends on the molecular properties of the plastic, and the thickness. Put two layers of the same plastic there, and it will rotate the polarisation by twice the angle. The angle can also depend on the wavelength, or colour, of the light. Some colours might be rotated by different angles, resulting in them appearing brighter or darker when seen through the entire setup. This is the source of the rainbow colour effects you sometimes see when wearing polarising sunglasses and looking at glass or transparent plastic surfaces.

This leads to another practical application of polarisation. If you do this with pieces of plastic such as rulers or protractors, you'll see coloured patterns, even though the thickness might be constant. These correspond to regions of the plastic where the molecular structure has been stressed by the manufacturing process. If you bend the plastic, you'll see the patterns change as the stress patterns within the plastic change. So you can use polarisation to examine stress regions in certain materials.

Another application is related to the sugar solution example mentioned above. Sugar (more specifically, common table sugar, or sucrose) is what is known as a chiral molecule, which means that the atoms are bonded together in such a way that the molecule does not have mirror symmetry. If you reflect the structure in a mirror, you get another molecule which cannot be rotated to match the original - like left and right hands. This asymmetry gives rise to the effect of rotating the plane of polarisation of light passing through the sugar.

Optically active plastic (a French curve) between crossed polarising sheets, showing stress patterns. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike image by Tom Paton, from Flickr. |

This means two things: (1) If you know beforehand that the sugar is entirely left-handed (or entirely right-handed), you can measure the concentration of the solution by measuring its effect on polarised light. (2) On the other hand, if you know the concentration of the solution, you can determine by the angle of rotation what percentage of the sugar is left-handed and what is right-handed.

Sugar is not the only chiral molecule which affects polarisation. Some molecules found in molecular clouds in space do the same thing. And what's more, some radiation sources in space are polarised, particularly radio sources. (Radio is an electromagnetic wave like light, so can also be polarised.) Here the polarisation is caused by magnetic fields. We can detect polarised radio waves with radiotelescopes. If we could measure how much the plane of polarisation has been rotated, we could measure the amounts of chiral molecules in molecular clouds between us and a radio source. We don't know the original plane of polarisation, however we can work it out, because the rotation angle varies with wavelength. By measuring the polarisation of several radio wavelengths, we can "unrotate" them by different thicknesses of molecules until they all match - and that allows us to measure the concentrations of molecules in deep space.

Difference between a scene photographed in normal light (left) and polarised light (right). Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike image by Andy Urban, from Flickr. |

Some insects, notably bees, can detect the polarisation of light. This allows them to navigate using the position of the sun, even when it's cloudy, since the polarised light of the sky penetrates the clouds. Human eyes cannot easily detect or distinguish polarisation, but we do have a very slight sensitivity to it. There is an experiment you can try to see if you can detect the polarisation of the sky, or a polarised display screen. It is borderline detectable - some people can see it and some can't. (I've tried and I'm not convinced I can detect anything. Maybe you will have better luck.)

Diagram of linearly polarised light (left) and circularly polarised light (right). The red line shows the electric field strength and direction as the wave propagates along the black axis. The green and blue waves show the components in the horizontal and vertical planes, respectively. Public domain image by Wikipedia user Dave3457, from Wikimedia Commons. |

Light can be made circularly polarised not by blocking one of the plane polarisation directions, but by slowing it down. Light slows down when it propagates through a material. (The "speed of light" which is constant in Einstein's relativity refers to the speed of light in vacuum.) The ratio of the speed of light in vacuum to the speed of light in a material is called the refractive index of the material. Water, for example, has a refractive index of 1.33, so light travels at only 75% of its normal speed when in water. Some materials have different refractive indices for two different orientations of plane polarisation because of asymmetries in their crystal structure. The most common such materials are the minerals calcite and mica. In general such materials are called birefringent.

Circularly polarised light (left) passes through a sheet of birefringent material which slows one component of the polarisation by a quarter of a wavelength, resulting in linearly polarised light, which then passes through a linear polariser. Circularly polarised light of the opposite orientation would be linearised at 90° and then blocked by the linear polariser. Public domain image by Wikipedia user Dave3457, from Wikimedia Commons. |

The thing with circular polarisation is you can undo it again, with another sheet of the same birefringent material of the same thickness. By retarding one of the components by another quarter wavelength, you synch them back up again, and return to what you began with. This effect is used in 3D movie glasses, which use filters made of a layer of birefringent material followed by a layer of Polaroid. These filter out circularly polarised light by converting it to plane polarised light first, then filtering through the Polaroid. The left and right sides of the glasses filter out circularly polarised light of opposite orientations, so you see the movie image intended for your left eye only with your left eye, and similarly for the right eye. This is superior to using plane polarised light for the two images, because if you tilt your head with plane polarised glasses you will partially mix up the images, whereas this doesn't occur with circularly polarised light.

So that's polarisation in a nutshell. A slightly bigger nutshell than the one Neil deGrasse Tyson gave on Cosmos. Like a coconut to his macadamia, baby!

[2]"Polaroid" is a trademark of the Polaroid Corporation, and so not strictly the correct generic term for such material. You're probably supposed to call it "polarising plastic material" or something, but everyone I know just calls it Polaroid.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |