| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of a glass sculpture}

1 Caption: Art of glass

|

First (1) | Previous (3360) | Next (3362) || Latest Rerun (2891) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3361.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Allow me the indulgence of starting with a story.

Island of Murano, Venetian Lagoon. |

On a trip to Venice with my wife, we were visiting the small island of Murano, a short ferry ride away in the Venice lagoon. Murano is famous for its glassworks, and is dotted with dozens of glassmaking, glass blowing, and glass working establishments, from large factories to individual artisans. We were browsing in one of the larger places, looking for a piece of glass artwork to decorate our home. As with any endeavour of this type, the thing you like the most turns out to be right at the breaking point of your desired budget. So we began the intricate dance of claiming that it was too expensive and we couldn't afford it, countered by the sales guy's claims that if he sold it for anything less his children would starve.

We bargained down a little bit, but it was still a lot of money. We dithered further, and finally the salesman, in desperation, said he would throw in free shipping. We knew that the shipping on this heavy and fragile item would cost a lot, so this represented a substantial discount for us, and we took the plunge and shook hands. Pleased with his sale, the man picked up the piece and carried it downstairs to the sales counter for us (it was quite heavy).

The Murano glass art we bought. |

Behind the counter was an older man, and all the bubble wrap, boxes, and more heavy duty padding needed for packaging works of glass for shipping. He exchanged some Italian with the salesman, asking what price we'd settled on. The salesman told him that he'd given us free shipping, and the old man nodded sagely, filled in something on an order form, then turned to us and asked in English, "And where do you live?"

I answered, "Australia." The old man immediately burst into a torrent of angry Italian at the salesman, which I fairly easily got the gist of: "You gave them free shipping to Australia! What were you thinking?! Why didn't you ask them where they lived first?!"

Thankfully he turned pleasant again when dealing with us and honoured the deal, and a few weeks later after we'd arrived back home the package turned up and our work of glass art had made the trip unscathed. It now sits proudly in the living room, catching the sunlight during the day and forming an integral part of our decor.

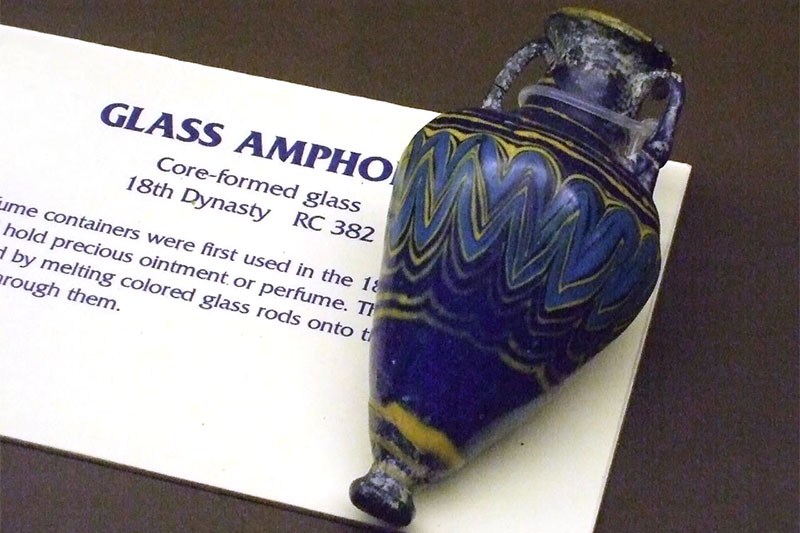

Example of Ancient Egyptian glass. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike image, by Mary Harrsch. |

Murano was established as a centre for glass making in 1291, when city officials banished the industry from the main islands of Venice because of the danger of fires. Glass itself has been around since the time of Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeologically, the origin of manufactured glass is murky, but seems to be around 3500 BC. By roughly 1500 BC, there was a small industry of glass making and forming, producing simple glass beads and ingots which could then be carved cold to form decorative or functional shapes. Some larger containers were made by making thin glass rods, which were then wound around a mould shape and heated until they fused. The mould was then removed, leaving a bowl or cup.

With the end of the Bronze Age, the art of glassmaking seems to have been lost amidst the social upheavals of history. It re-emerged around 900 BC, again in the eastern Mediterranean region, and has been with us ever since.

This ancient glass was very different to the sort of thing we think of these days when we hear the word "glass". It was hard and brittle like modern glass, but looked more like the lumps of naturally occurring volcanic glass known as obsidian, formed by the heat of volcanic activity. Glass is primarily made of silica, the mineral in sand, a simple compound of silicon and oxygen. To form glass you essentially melt a bunch of sand, then let it cool down into an amorphous lump. The problem was that sand typically has many impurities in it, which produce discolouration and opacity. Although a useful material for its strength and hardness properties, it wasn't clear.

Examples of Ancient Roman glass. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike image, by Carole Raddato. |

The Ancient Romans made many things from glass, and within the Judean reaches of the Empire glass workers developed the technique of glass blowing, in the first century BC. By taking a blob of molten glass on the end of a metal tube, you could blow air into it, blowing the glass into a hollow bubble. This revolutionised the production of glass vessels and the technique spread rapidly, as did the resulting products.

The next breakthrough came about a century later, when glass workers in Alexandria discovered that mixing in some of the mineral known today as pyrolusite (an ore of manganese) would make a batch of glass clear and relatively colourless. This opened up wondrous new uses for the material, as it was the first hard, clear material that humans had ever had available in any appreciable quantities. It could be used to cover holes in walls, blocking wind and cold, without blocking light. And thus were born glass windows. It took hundreds more years before glass became common enough to be used in average buildings, but the rich and elite adopted it for ceremonial buildings and privileged residences.

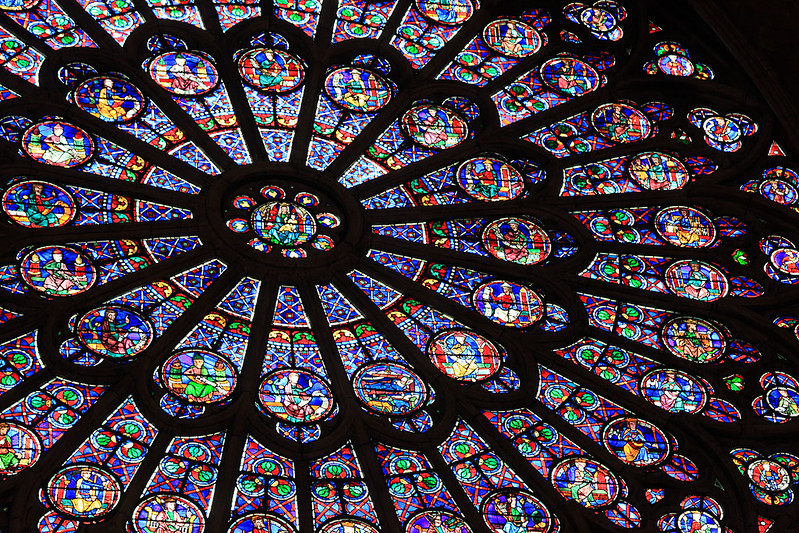

Stained glass. The Rose Window of Notre Dame de Paris. |

Making a large, thin sheet of glass to use as a window is non-trivial, and it took some time to develop the techniques which could do so reliably. Early windows were small, or made of multiple small pieces of glass held in latticework frames made of lead. The glass was bubbly and wavy and distorted the light passing through, so many windows admitted light, but not a view. Architects and artists made the most of this by using coloured glass, made by adding various minerals to the mixture, to form patterns or pictures which would be illuminated by external daylight. Such stained glass windows are still a feature in many churches and occasionally other buildings.

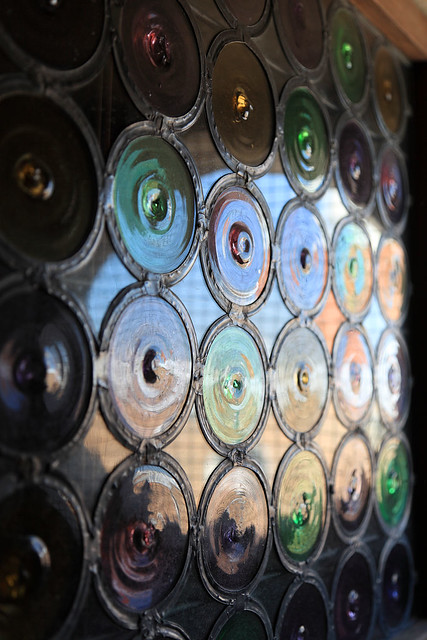

In the 1300s, French glass workers developed a technique in which they would blow a bubble of glass, then flatten it on an iron plate and spin it like on a pottery wheel. The still fluid glass flowed out to form a flat round disc. The disc was of uneven thickness, being thinner near the edges and rising to a distinct lump, or crown, in the centre. Known as crown glass, the resulting sheet could be cut into pieces suitable for windows. The flatter parts near the edges were more valuable and used for larger windows, while the lumpy bits near the middle could be used as smaller decorative elements.

Central parts of crown glass used for decorative window. |

If you take an edge piece of crown glass cut into a rectangle for mounting in a window, it would be thicker at one end and thinner at the other end. For stability reasons, these were mounted with the thicker side down. So many old windows have panes of glass which are thicker at the bottom than at the top. This may be the source of the myth that glass is a "liquid" which flows and oozes downwards slowly over many years. Glass is by any sensible definition a solid, and is in fact harder and more rigid than most materials which people happily call solids, including most metals. It doesn't flow or ooze noticeably over anything less than millions of years. (A study published in 2010 indicates it might sag a really tiny amount, but the authors are not convinced that that's what they've measured, as the amount of deformation observed is only a few nanometres.)

Several other methods of producing reasonably flat glass appeared over the centuries, but they all had noticeable imperfections, resulting in slightly wavy or bubbly surfaces. You could see through windows like this, but the view would be noticeably distorted. Really flat panes of glass had to be ground and polished into shape at great expense, until the invention of the float glass technique in the 1950s. In this technique, molten glass is floated on a layer of molten metal (usually tin), allowing it to stay liquid long enough to settle into a beautiful flat surface before cooling.

Flat panes of modern glass. |

The structure of glass is an amorphous non-crystalline solid. The silicon and oxygen atoms in it are mixed up in a random jumble, rather than being arranged regularly in a repeating crystal structure. By heating or cooling parts of the glass at different rates, or by introducing small amounts of other elements, the glass can be given an amazing array of properties. The surface can be hardened to resist scratches, while the core can be made less brittle to resist breaking. For the greatest strength glass can be laminated with thin layers of plastic, which provide structural integrity even if the glass is shattered.

Made thin enough, glass is flexible. Drawn into narrow fibres, glass can bend and flex like wire, and play a role similar to electrical wiring to carry signals and data. Because of the refractive phenomenon of total internal reflection, light shining in one end of a long, thin fibre made of glass bounces around inside the fibre, never emerging until it reaches the far end. And because we can switch light on and off extremely quickly, many millions of times per second, we can use this to transmit data. Such optic fibres are more efficient and more secure than data transmission over metal wiring.

Modern architectural glass. Hauptbahnhof, Berlin. |

Because it is transparent, glass feels light and airy to our visual sense (despite the fact that it is quite a heavy material). Modern architecture makes good use of this quality to give our tall buildings a sense of graceful lightness rather than heavy gloom. Glass objects catch the light and bend it in interesting ways which draw our eyes. So glass is used for a variety of functional objects, and also for artistic purposes. The works of Dale Chihuly and others who render their imaginations into solid form with glass illustrate just how spectacular and beautiful such things can be.

And so we return to Murano and the history of glass. You can see many showrooms of beautiful art glass in Venice itself, but to revisit the history of this amazing material, take the trip across the lagoon to Murano, where you can see the glass museum. Thankfully the depiction of it being smashed to pieces by James Bond in Moonraker was a fiction (the movie also took liberties with its location, shifting it to near St Mark's Square in Venice itself). Because history and reality are often more beautiful and interesting than fiction.

Glassmaking is also the first practical application of nanotechnology. The Lycurgus Cup dates from Roman times and is made of dichroic glass, showing a different colour in reflected and transmitted light. It's due to a suspension of gold and silver nanoparticles in the glass, although modern science isn't sure how they got there.Medieval stained glass windows also contain nanoparticles. Silver nanoparticles give a gold colour, and gold nanoparticles give every colour except gold. I'm pretty sure the cathedral glaziers didn't know what was happening, just the results they got when they added gold or silver to their melt.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |