| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 {photo of an abstract artwork}

1 Caption: Taming particles

|

First (1) | Previous (3312) | Next (3314) || Latest Rerun (2895) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Annotations theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3313.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Water, fire, air, and earth. Creative Commons Attribution image by Gunjan Karun. |

But then we discovered the secret of radioactivity, and it led us to the fact that the atoms we had thought were indivisible were actually made of smaller particles: electrons, protons, and neutrons. In fact, every atom of every one of the hundred-odd elements was made of just these three particles, arranged in different quantities and ratios. The constituents of reality had become simple again, but in a way that the Ancient Greeks could never have imagined.

But then the methods we used to learn more about protons and neutrons and electrons started to reveal other sorts of particles: muons, neutrinos, W bosons, π (pi) mesons (also called pions), K mesons (or kaons), swarms of other different sorts of mesons and baryons. We were back to complexity again.

I haven't discussed all of these different particles before, so let me take a single step backwards at this point. The invention of cloud chambers, particle accelerators, scintillation detectors and various other bits of equipment that let us examine particle interactions led to unforeseen discoveries. Nobody can predict everything that will be discovered when we find new ways to observe nature, and so it was with the tools we developed to understand subatomic particles. These detectors and the physics of collisions allowed us to determine the masses, electric charges, and angular momenta of the particles involved in various reactions.

Every so often, a particle with previously unseen properties appeared. Most of them tended to be heavier than protons and neutrons. The new particles could be split into two classes based on their spin angular momentum. Those with integral spin (i.e. 0, 1, 2, etc.) tended to be less massive, and these were collectively dubbed mesons. Those with half-integral spin (i.e. 1/2, 3/2, 5/2, etc.) tended to be more massive, and these were collectively dubbed baryons. (There were also leptons, which are a different class of particles again, being much lighter in mass, and which we have discussed before.)

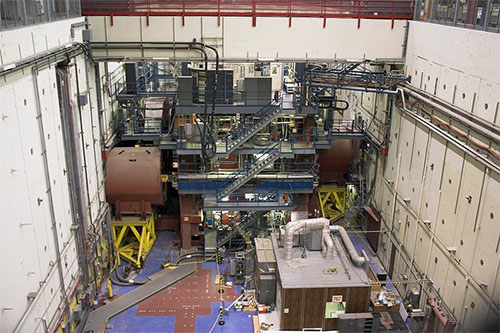

Stanford Linear Accelerator, a big machine to probe small particles. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike image by Justin Lebar from Wikimedia Commons. |

An early new baryon was called the Λ (lambda) particle, discovered in 1950. It was electrically neutral like a neutron, and a little bit heavier than a neutron. It was unstable and decayed into either a neutron plus a neutral π meson, or a proton plus a negative π meson. This decay reaction fit with the theories of the time, except that the lifetime of the Λ particle before decaying was strangely long. The theory predicted the particle would decay after just 10-23 seconds, but instead it survived for 10-10 seconds. This might not sound like a big deal, with both of these times being much smaller than a second, but the magnitude difference is enormous. It would be like the theory saying something should happen in one second, but when measured it takes over 30,000 years.

Then things got even more confusing. The new particles tended to fall into small groups with similar, but not identical properties. For example, there was a group of four baryons of almost identical mass, just a bit heavier than a proton or neutron, with identical spins of +3/2 (protons and neutrons in contrast have spin +1/2), but with different electric charges. These were called Δ (delta) particles, and came in electric charge -1 (the same as an electron), 0 (like a neutron), +1 (like a proton), and +2 (remember that +2 electric charge on a single particle - that's weird). These Δ particles decayed in about 10-23 seconds into either a proton or a neutron, plus a π meson of appropriate electric charge to make the charges balance. Their short lifespans before decay were consistent with theoretical expectations.

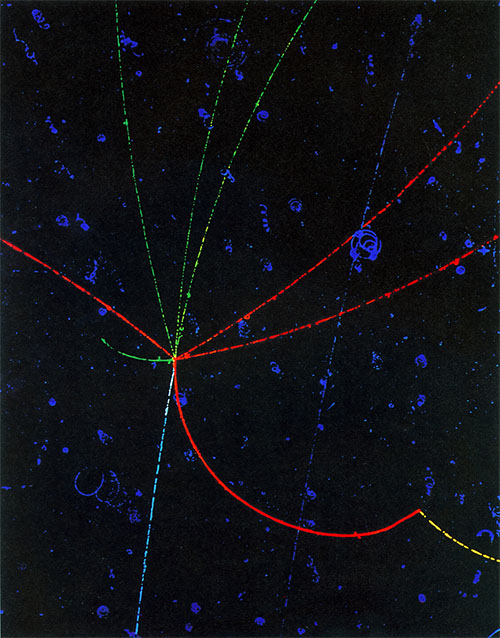

Particles tracks in a bubble chamber. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike image by Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. |

The spin 1/2 Σ particles produced another bit of strangeness, though. They decayed into protons and neutrons, plus π mesons, but how they did so was decidedly odd. The neutral Σ decayed quickly (in about 10-20 seconds) into a Λ particle and a gamma ray which carried away the excess mass-energy. The negatively and positively charged Σs, however, showed the same anomalous slow decay as the Λ, taking 10-10 seconds to decay into a proton or neutron plus an appropriately charged π meson. So these charged Σ particles could decay only slowly into protons and neutrons, while the neutral Σ could decay rapidly into a Λ, but this Λ particle then required a slow decay down to a proton or neutron. This huge difference in decay times was puzzling. Electric charge was conserved, baryon number was conserved, there seemed to be no reason for this strange slow decay of the Σs and Λ into protons and neutrons.

The next step in science after making observations that don't fit the current theory is to come up with some hypothesis to explain them. In this case, the idea was proposed that there was not just one physical mechanism by which baryon decay occurred, but two different mechanisms with different properties. One was the expected decay which happened quickly, the second was a new, slower type of decay which occurred when the first type of decay could not. The first mechanism was seen as "strong", and the second one as "weak". The strong interaction produced the normal decays, while the weak one produced the "strange" slow decays.

The particles themselves could now be seen as either "normal" or "strange". Protons, neutrons, and Δ particles were normal, while the Λ and the Σs were strange. A normal particle could decay rapidly to a normal particle, or a strange particle could decay rapidly to another strange particle (a neutral Σ decaying to a Λ), but a strange particle decaying to a normal one could only decay slowly, via the weak mechanism. So the strange particles could be seen as having a property, like electric charge or baryon number, which is conserved in strong decays, but may change in weak decays. Protons, neutrons, and Δs have strangeness zero, while Σs and the Λ have strangeness -1 (it was chosen to be negative rather than positive for historical reasons, the sign doesn't really matter).

Additional evidence for this view of the interactions was the discovery of the Ξ (xi) particles. These form a family like the Σs, being slightly heavier baryons in two groups of two: spin 1/2 with charges 0 and -1, and spin 3/2 with charges 0 and -1. But unlike the Σs, there was no Ξ with charge +1. The spin 3/2 Ξs decay rapidly to the spin 1/2 versions plus a neutral π meson, while the spin 1/2 Ξs decay slowly to a Λ particle plus a π meson of appropriate charge. The fact that the Λ is already strange (strangeness -1) implies that for this decay to be slow, the Ξ particles must be doubly strange (strangeness -2). They are probably not strangeness 0 because they do not decay directly into protons and neutrons at all, but must take a decay path via the singly strange Λ.

So now (historically speaking, in the 1950s and early 1960s when all these new particles, and many more besides, were being found) we were in a state where the simple elegance of a world constructed of just three particles - proton, neutron, and electron - had been expanded once more into a vast menagerie of other particles. Now we also had a slew of other baryons, with this "strangeness" property that had been invoked to explain otherwise inexplicable slow decay times. There was also a slew of different mesons which had also been discovered and that I have glossed over until now: π mesons in charges of -1, 0, and +1, neutral η mesons, K mesons in charges -1, 0, and +1, all of these having spin 0; then another group of mesons like these, but with spin 1: ρ mesons in three different charges, neutral ω and ψ mesons, and another whole set of K mesons. All together, there were well over a hundred different "elementary" particles.

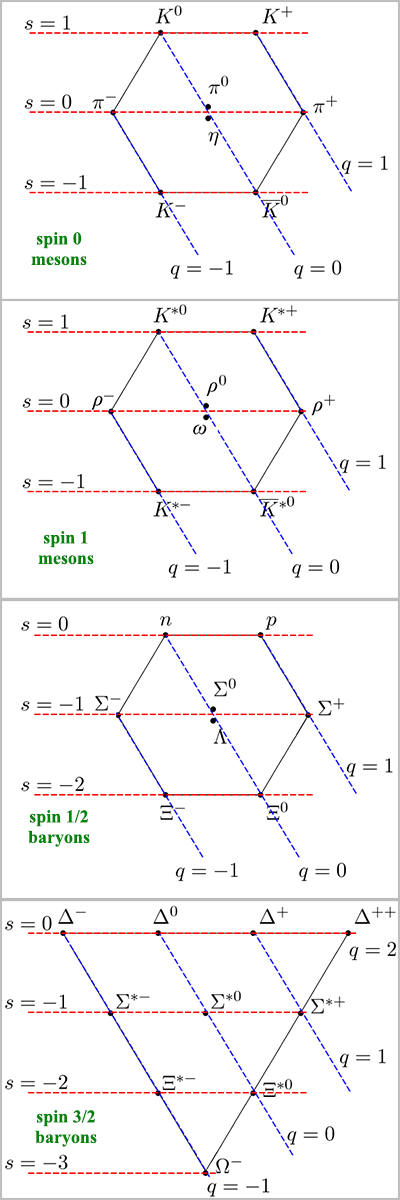

Gell-Mann's Eightfold Way classification of mesons and baryons. q is electric charge, s is strangeness. Based on Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike images by Laura Scudder from Wikimedia Commons. |

In 1961, Murray Gell-Mann and, independently, Yuval Ne'eman came up with a classification system which seemed to impose a similar sort of order to the periodic table on to the collection of mesons and baryons. Gell-Mann called it the Eightfold Way, alluding to the Eightfold Path of Buddhism, because the arrangement included groupings of eight mesons and eight baryons into geometrical arrangements according to their properties.

The classification began with the spin 0 mesons. Gell-Mann placed the mesons in a two-dimensional grid, separated along one axis by electric charge, and a second axis by strangeness. Doing this formed a hexagon (which could be made regular by making the axes intersect at 60° instead of 90°):

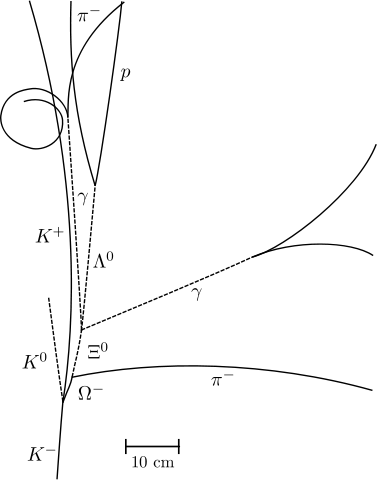

Particle track tracing of the first detection of the Ω baryon. Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons. |

Gell-Mann didn't stop there, either. Also in 1964, he developed a deeper explanatory layer to his model. (George Zweig also independently developed a very similar model around the same time.) Gell-Mann proposed that all of the mesons and baryons in his four diagrams were composed of smaller constituent particles, which he called quarks, taking the name from a line of nonsense verse in the book Finnegans Wake, by James Joyce. The really neat thing was that every single meson and baryon could be explained by the existence of just three different types of quark. Gell-Mann defined them as:

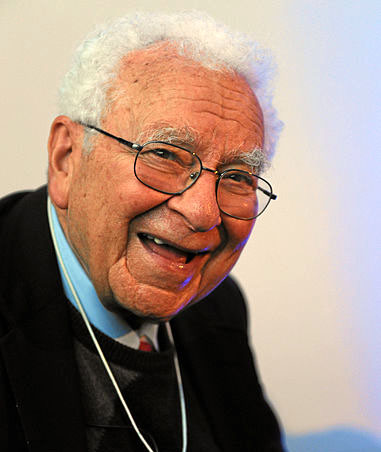

Murray Gell-Mann. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike image by Connormah from Wikimedia Commons. |

Gell-Mann's quark model was bold and sweeping in its scope and explanatory power. But was it true? In 1968, researchers at the Stanford Linear Accelerator were performing experiments to find out. In a method very similar to how Ernest Rutherford discovered the atomic nucleus, they were firing particles at protons to see if they had any internal structure. The scattering results of the experiment showed that a proton was not a simple sphere-like particle, but that it was more like an empty ball with very tiny point-like centres of concentrated mass and charge within it. The proton was not a single particle - it was made of something smaller.

A year later, in 1969, Gell-Mann was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his unravelling of the particle zoo, and the quark model which explained the vast abundance of mesons and baryons with a smaller number of more fundamental particles. This was a rather quick award by the Nobel Committee, but their boldness was borne out in subsequent experiments which have cemented the quark model's place in physics.

There is more to say about the quark model (in particular, three additional types of quark which were discovered later), involving such whimsical terms as charm and colour, but I have run out of time this week. Another point to be aware of is that leptons, the class of particles that includes electrons and neutrinos, are not made of quarks. But leptons come in nowhere near as many types as the mesons and baryons. There are only six different leptons, as there are six different quarks, and the overall situation is still relatively simple compared to collections of hundreds of particles. From order (the Greek elements), to chaos (chemical elements), back to order (the periodic table and atomic structure), then to chaos again (the particle zoo), Gell-Mann and his contemporaries restored order once more to our understanding of the nature of matter.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |