| Archive Blog Cast Forum RSS Books! Poll Results About Search Fan Art Podcast More Stuff Random |

|

Classic comic reruns every day

|

1 Mercutio: I've got an idea for a horror movie. I'll pitch the concept, you can write the script.

1 Shakespeare: Cool.

2 Mercutio: A young couple have a chance encounter playing Pokémon Go, start a relationship, and travel the world in search of exotic Pokémon.

3 Mercutio: After a humorous misunderstanding they split up and spend the middle act angry at one another. Then they bump into each other hunting a rare Pokémon and reconcile!

4 Ophelia: How is this horror? What's spooky about it?

4 Mercutio: The Pokémon aren't really there...

|

First (1) | Previous (3506) | Next (3508) || Latest Rerun (2876) |

Latest New (5380) First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 Shakespeare theme: First | Previous | Next | Latest || First 5 | Previous 5 | Next 5 | Latest 5 This strip's permanent URL: http://www.irregularwebcomic.net/3507.html

Annotations off: turn on

Annotations on: turn off

|

Pokémon Go was released just this past week. There's already a lot of news about it, and the potential for unfortunate accidents it creates.

I like to think it might also lead to some happy accidents.

But let's think a bit more closely about how colour vision works, and try to understand what a pair of glasses could possibly do to rectify colour blindness. To recap from the beginning:

Colour is a psychophysical property related to human visual perception. The distinctive appearances of what we know as colours are really produced by neurological responses in our brains to the stimulation of retinal nerve cells in our eyes, by particular wavelengths of light.

People often think of colours as directly, physically related to the wavelengths of visible light. Light is an electromagnetic wave, propagating through space, or through a transparent medium such as air or water. A light wave is really just an electric field and a magnetic field, oscillating back and forth in sync with one another. The resulting ripples in the two fields spread outwards from the source of the light, pretty much like ripples in a pond[1]. They spread at the speed of light, which is ridiculously fast.

The electromagnetic waves of light have a physical property called the wavelength. This is the distance between successive peaks (or equivalently, successive troughs), of the wave. For visible light, the wavelength is very small, ranging between roughly 400 and 700 nanometres, a nanometre being one millionth of a millimetre.[2] The wavelength of light determines what colour we experience when we see it. Light of the short wavelengths around 400 nm appears violet or blue, light around 550 nm appears green, and towards 700 nm the light appears orange or red.

The important thing is that the colour that any particular light appears to be is not a physical property of the light itself. Rather, it is the perceptual feeling we experience in our brains when our eyes sense the light. Although in common parlance we say that light of wavelength 550 nm "is green", the greenness of that light is not a property of the light itself, it is a property of how our brains sense and react to light of that wavelength.

A way to understand this is to think about the way that our eyes sense light and our nervous system (including the brain) processes colour. I've talked about this in some detail before, so I'll skim the highlights here and refer you to my previous annotation for a little more depth.

Light is detected by specialised nerve cells in the retinas of our eyes. Incoming light waves excite electrochemical signals in the cells, which get carried to the brain via the optic nerve. Most humans have four different types of receptor cells. One type is called rod cells because of their cylindrical shape. Rods are sensitive to all wavelengths of light, so don't provide any discrimination with wavelength - they merely indicate levels of brightness. If you only had rod cells, you would quite literally see in black and white.

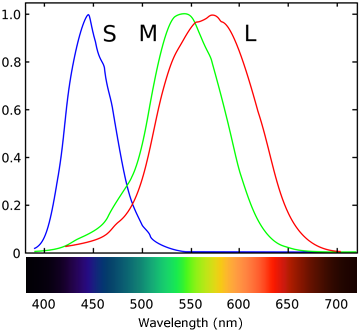

The other three types of receptors are called cone cells because they are conical, and these are divided into what are called L-cones, M-cones, and S-cones. The L, M, and S stand for long, medium, and short, referring to the different wavelengths of light that they respond to. An L-cone is stimulated by long wavelengths of light, which we would sense as red or orange, but not by short wavelengths, that we would experience as blue. Similarly, an S-cone is stimulated by short wavelength light, which we sense as blue or violet, but is not stimulated by the long wavelength light that we perceive as red.

Figure 1. Responses of cone cells to different wavelengths of light. Based on a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike image by Wikimedia Commons user Vanessaezekowitz. |

The question now arises: If we only have three types of colour receptive cells, how do we experience the range of hundreds or thousands of different hues? Violets, blues, purples, greens, cyans, yellows, oranges, reds, mauves, magentas, and all the finely graded shades in between? The answer lies in the relative strengths of the cone cell responses to different wavelengths of light. The longest wavelengths of visible light stimulate the L-cones of your eye quite strongly, but the M-cones and L-cones not at all. We perceive this a a deep, rich red colour. Make the wavelengths a little bit shorter, and now the light begins to stimulate the M-cones a bit as well. Our brains interpret this mixture of signals from the L-cones and M-cones as a more orange-red colour. Make the wavelengths shorter still and it stimulates the M-cones progressively more, and eventually the stimulus to the L-cones starts to fall off. We are now into the realm of yellow shades, and moving towards green. When the wavelength shortens to around 550 nm, it primarily stimulates the M-cones, with some stimulus to the L-cones and the S-cones. A signal like this from our eyes, strong M response and weak L and S responses, is interpreted by our brains as green.

And so it continues down the spectrum. For any given single wavelength, there is a unique mixture of stimulus strengths from the L, M, and S cones. This combination of signal strengths gives our brain the information it needs to perceive each wavelength as a different hue of colour. As a specific example, notice that light of wavelength near 580 nm, which is a wavelength that we perceive as yellow, stimulates both the L and M cones roughly equally. The psychophysical sensation of "yellow" in our brains is generated not by "yellow detecting" cells, but by a roughly equal stimulus of the L-cones and the M-cones. This can be achieved by a wavelength in between their respective peak sensitivities. However, it could also be caused by stimulating the L and M cones equally in some other way.

This explains how colour display screens work to reproduce something close to the full range of colours that humans can perceive, but with only microscopic red, green, and blue light emitting components. To produce a sensation of "yellow", you don't actually need what might be called "yellow light", that is to say, light with a wavelength close to 580 nm. What you need is to stimulate the L-cones and the M-cones roughly equally. Yes, you can do this with "yellow light" of wavelength close to 580 nm, but you can just as well do it with a mixture of light with wavelengths near 550 nm and 650 nm ("green light" and "red light").

This is what display screens do. If you display a bright yellow image on a screen, and then look closely with a magnifying glass, you will see that there is no yellow on the screen at all. The yellow colour you perceive when viewing the screen from a distance is actually a mixture of microscopic dots of red and green. When seen from a distance, these two different wavelengths stimulate L-cones and M-cones that are physically close enough on your retina that your brain interprets the stimulus in exactly the same way as it does when looking at an area which is emitting "yellow light". By controlling the relative brightnesses of just three different wavelengths, a display screen can stimulate exactly the same responses in our visual system as almost the full range of visible wavelengths. Try as you might, with your naked eye you cannot tell the difference between light of a pure wavelength perceived as yellow, and any of several different mixtures of "red" and "green" light - because they all stimulate your retinal cells in exactly the same way.

However, there is a physical difference between pure "yellow light" and a mixture of "red light" and "green light" that stimulates our cone cells in the same way and so appears to be the same shade of yellow. Even if it's impossible for us to tell the difference with the naked eye, we can easily tell the difference with scientific instruments. Something as simple as a glass prism will do the trick, in fact. Spread the light into a spectrum, and you can soon see the mixture of wavelengths that make it up, be it pure yellow, or a mixture of red and green.

This suggests an astonishing thing. Humans are all colour blind. Imagine that we had four different types of cone cell, each responding to different ranges of wavelengths. Then it would be possible that we could distinguish "yellow light" from a mixture of "red light" and "green light". A human with four different types of cone cells would see these two things as different colours, whereas a normal human would see both as exactly the same shade of yellow. I can't tell you what the other colour would look like, because neither you nor I have the sensory experience to relate to such a thing.

And why stop at four types of cone cell? You can imagine having five, or seven, or twenty, or a thousand. A hypothetical being with a thousand differently tuned colour receptor cells would have immensely discriminating colour vision. They might be able to look at a vast forest where a human just sees all of the leaves as pretty much the same green colour, and instead see every species of tree as a highly distinct colour, maybe even every single leaf as an easily distinguishable colour. This could be very useful for tasks such as hunting or gathering food. The downside is that to build a convincing colour display screen for such a creature, you'd need a thousand different coloured light emitters, rather than just the red, green, and blue that serve for us humans.

This extrapolation is not entirely fanciful either. It is known that most, if not all, species of birds in fact have four different kinds of cone cells in their eyes. And mantis shrimp have sixteen. There is some evidence that a very few humans have a mutation which gives them four different types of cone cells too. Such people and animals see far more different colours than normal humans, and we are in a very real sense colour blind compared to them.

Which brings us to actual colour blindness. Colour blindness is typically a hereditary mutation in the genes that control the development of the cone cells during foetal development[3]. The genes affecting development of the L and M cones happen to be on the human X chromosome, which is also involved with sex determination. Males have one X and one Y chromosome, and a cone cell mutation appearing on the X chromosome will affect colour vision. Females have two X chromosomes, and both have to have the same mutation for colour blindness to appear - if only one carries the mutation, the unmutated chromosome compensates for the deficiency. So males suffer colour blindness significantly more than females do.

There are a few different types of colour blindness that can result from genetic causes:

Let's talk about the most common two types of colour blindness, which affect either the L or M cones. A deficiency in either of these cells results in difficulty telling apart colours that most people perceive as red or green. A protanope or deuteranope, as people with these deficiencies are referred to, has what is commonly known as red-green colour blindness. (Deficiency in the S cones produces the much rarer blue-yellow colour blindness.)

The problem is that red objects typically don't reflect (or emit) only "red" light (wavelengths above 620 nm or so), and green objects don't reflect only "green" light (wavelengths around 550 nm). Objects usually reflect a broad range of wavelengths. If the range is skewed more heavily towards red, the L and M cones in a non-colour-blind person's eyes produce a mixture of signals skewed that way, and their brain senses "red". Likewise, if the range is skewed more towards green, the cone cells produce a signal skewed that way, and their brain senses "green".

A deuteranope or protanope, however, gets a muddled and less distinct mixture of signals from the L and M cone cells. Because of the inefficiencies in one or another of the cells, the resulting signal to the brain tends to be a more even mix of stimuli over a greater range of different wavelength distributions. The result is that a red object and a green object both appear somewhat similar, because the L and M stimulus levels are not sufficiently different to enable the nervous system to tell them apart easily. To a person with full colour vision, red and green objects look completely different, and they would never confuse one for the other. To a deuteranope or protanope, red and green objects look like slightly different shades of the same colour. It's not the miles apart that red and green are to most people - it's more like two similar shades of brown.

Is there anything that can be done about this? It turns out there is! The wavelengths reflected by most red and green objects actually overlap to a significant degree. It's mostly this overlap region that the deficient L or M cones of deuteranopes and protanopes respond to, which is what results in the muddying of the two different colours in their neural response. Normal L and M cones react more to the different ends of the ranges than to the overlap region, resulting in the strong psychophysical distinction between red and green for most people.

So what if we got rid of the overlapping wavelengths? Imagine we took a range of typical red objects and green objects, and located the wavelengths where objects of both colours reflect light, and then designed a filter to remove those wavelengths. Then a green object seen through such a filter would have the more reddish components of light filtered out, while a red object would have the more greenish components of light filtered out. To a person with normal colour vision, many green objects seen through such a filter would appear to be slightly more vivid shades of green, while many red objects would appear to be slightly more vivid shades of red. Not a great difference, but you might notice it.

But to a person with deuteranomaly or protanomaly, the removal of those overlapping wavelengths could make a big difference. Rather than the overlapping wavelengths of the red and green objects stimulating the L and M cones similarly, and thus appearing to be slightly different shades of a similar colour, now the red objects stimulate the L cones significantly more than the M cones, and the green objects stimulate the M cones much more than the L cones. But... this is exactly what happens to a person with normal colour vision!

In other words, by filtering out a carefully selected range of wavelengths, we can stimulate the L and M cone cells in deuteranomalous and protanomalous people in a similar way to those of people with normal colour vision. And the rest of the nervous system works the same way as in people with normal colour vision. It will take these stimuli and interpret them - as colours that look more different than they did prior to filtering. A deuteranomalous or protanomalous person could well see red and green objects through such a filter as two more obviously different colours, rather than shades of a similar colour.

And this is exactly what EnChroma glasses do. If you look at their technology explanation page, you will see (about 2/3 of the way down) a wavelength diagram showing the overlap of spectra of red and green objects, and overlaid on it the light blue "notch" where their lenses remove wavelengths of light. They also remove a notch between green and blue to address the rarer tritanomaly.

Searching online brings up a lot of testimonials and reviews by colour blind people who tried EnChroma glasses. These range from the speechlessly emotional, through the middle of the range, to the distinctly underwhelmed. The thing is, everyone's colour blindness is slightly different, and the wavelengths blocked by the glasses will result in different subjective effects for different people. So while some colour blind people will get a very obvious, almost startling effect, and suddenly be able to see and distinguish colours they couldn't before, others will get a smaller effect and may not be so impressed by it. Furthermore, the glasses only work for people with anomalous colour vision, in which all the cone cells are present, but not working normally. The rare people completely missing one of the sets of cone cells will get no benefit from EnChroma glasses.

So, if you're colour blind, and wondering if EnChroma glasses work and if they are for real, then the answer is a qualified yes. The science is real, and they definitely can assist some colour blind people to experience a richer world of colours, and to more easily distinguish red and green objects. But every individual's experience will be different.

I don't work for or represent EnChroma, but if I were colour blind, I know I'd want to at least give the glasses a try.

[2] Electromagnetic waves also exist with wavelengths outside this range, but they are not visible as light. Wavelengths shorter than 400 nm include ultraviolet, x-rays, and gamma rays at successively shorter wavelengths. Longer than 700 nm are infrared, microwaves, and radio waves. Radio waves can have wavelengths of several metres or more.

[3] Colour blindness can also sometimes be caused by brain or retinal damage, caused by trauma, exposure to ultraviolet light, or disease.

|

LEGO® is a registered trademark of the LEGO Group of companies,

which does not sponsor, authorise, or endorse this site. This material is presented in accordance with the LEGO® Fair Play Guidelines. |